Thursday, 7.26pm

Sheffield, U.K.

Postmodernism was a reaction to modernism. Where modernism was about objectivity, postmodernism was about subjectivity. Where modernism sought a singular truth, postmodernism sought the multiplicity of truths. – Miguel Syjuco

How do you sell a pen to someone?

You’ll remember something like this in The Wolf Of Wall Street.

The chap the film is about, Jordan Belfort, built his reputation on his skill at telephone sales back when telephones were a thing.

And he still teaches how to sell these days – it’s the way that the books teach you how to do it and it’s the way many trainers set out their material.

The video I was watching yesterday of Larry McEnerney from the University of Chicago described a few models of knowledge that are worth knowing about.

One form of knowledge is believing that what you know is right.

For example, if you write a business plan or a sales letter – you believe that what’s in there is correct.

If someone doesn’t agree with you, then you feel the need to explain yourself – defend your position.

In this model you’re right because you know what you know.

Maybe you’ve created a new system, a different way to do something, an improvement on a method – this must be good, right?

Well, it is in a positivist system, one where there is objective truth and you’ve just found it.

You’re told by people who think this way that you have to believe in your product – you have to have a kind of missionary zeal.

You must believe, if you are to sell.

Another form of knowledge is believing that you get the big picture – and know you’ve found a gap.

All this stuff exists and you know about it – you know what the problems are and so you can see a space where you can create a product.

But sometimes spaces exist because there is nothing of value in that space.

This kind of thing assumes that knowledge is bounded – you can put a box around it and see what is not there.

Both these approaches are at the heart of the way we’re taught to express ourselves for much of our lives.

You’ve created something new or spotted a gap in the market – well then, you must have a business.

You must have found something useful.

Well… not exactly.

A more current model of knowledge – a post-modern version – is one that’s based around the idea that knowledge is what people who should know agree is knowledge.

Knowledge emerges from the interactions of a community – and sometimes they accept new ideas and sometimes they discard old ones – and all the time they decide what is right and wrong.

That’s right – it’s not objective truth but the subjective views of people that create the truth.

What does that mean in practice?

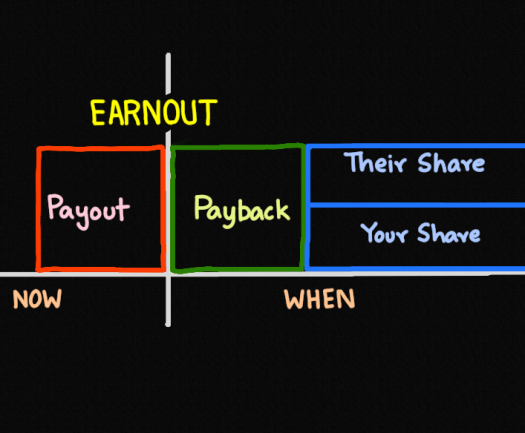

It means that if you try and sell someone an idea because you think it’s a good, new one, or because you think there is a gap in the market you’ll often find that the majority of people back away from you.

And that’s because their world is created by the voices of their community – the people in the business they work with, the managers, the leaders.

And before you can effectively sell to them you need to know what they are saying.

You have to start by listening – not by selling.

It’s only by listening that you’ll start to see how the people you’re selling to see the world.

And when you do that you can appreciate their point of view – and then add your contribution.

If you acknowledge what they know, show that you have listened and you care – then they might be willing to give you a change and listen to you in turn.

We live in a world that’s increasingly a collection of communities, of tribes, each creating their own knowledge worlds.

If you’re not in that world, you’re a tourist – so don’t expect to be taken seriously until you make an effort to integrate.

And that starts by being willing to listen.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh