Every industry is being transformed by digital technologies in front of us right now.

The overlay of information and abstraction onto the products and services we use every day creates new experiences, expectations and possibilities.

While we see and talk about this often in the context of entertainment, advertising, social media and mobile technology the industries that feed, move and power us – agriculture, transportation, utilities among others – are also being transformed.

So, how can we think about this changing environment and where we fit into it?

Professor Venkat Venkatraman is the David J McGrath Jr Professor of Management and the Chairman, IS Department at the Boston University Questrom School of Business and writes about the interface between strategic management and digital technology.

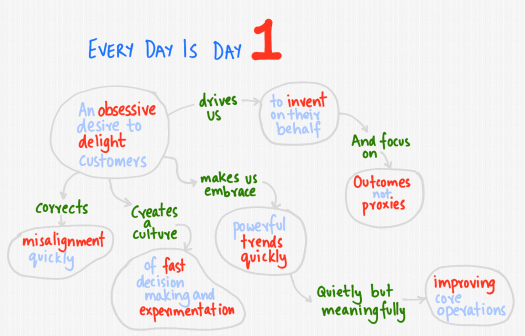

His book, The Digital Matrix: New Rules for Business Transformation Through Technology, explores the kinds of companies that play in this changing business landscape, what changes and transformations they will experience and the strategic moves they can make to win.

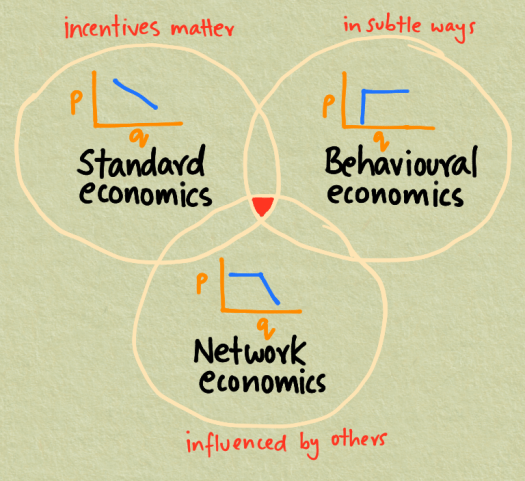

Venkatraman says in an interview with Antoine Abou-Samra that we often use two main ways to think about situations.

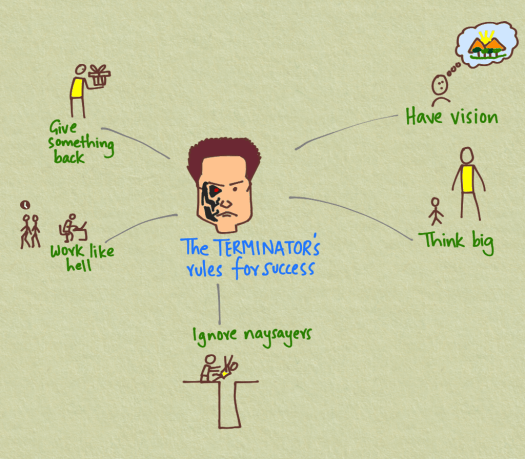

First, we look at successful companies and see what they did and the lessons they might have for us.

Or second, we look at new technologies such as Blockchain or digital tracking and imagine the implications they might have for us.

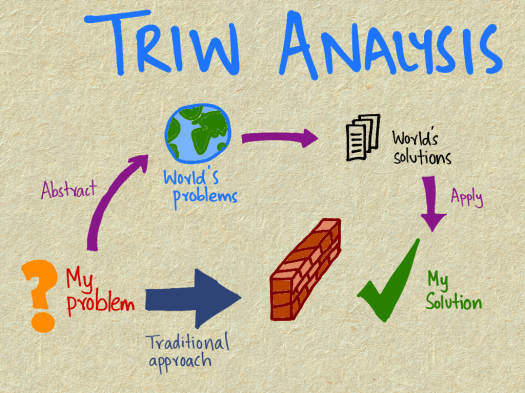

Venkatraman argues what is needed is to have a framework that can be used to understand the players and the actions they might take, and use that to inform and position ourselves strategically.

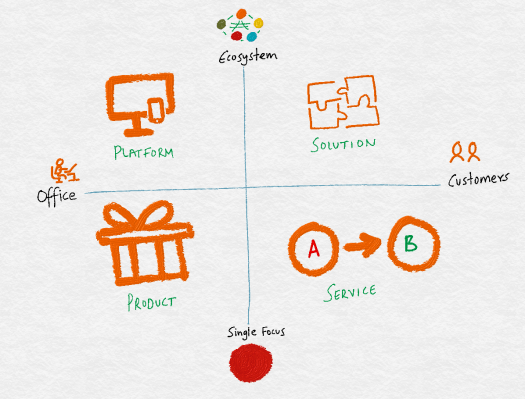

An interesting framework that can be used to understand which business model we are using in the digital age is shown in the picture above, adapted from this summary.

Traditionally, we think about the business we are in and whether we provide a product or a service.

This single focus on ourselves and what we do has been how business has been done for a long time. We make something – a product – or we help someone get from one point to another – a service.

Products are developed in the office while services are provided to customers.

Digital extends this simple matrix upwards to turn us from a small village of trades to a global market for anything we want.

Two new types of models emerge in this space.

Platforms aggregate and put forward options we can select from and Solutions address complex and ‘wicked’ problems that we face.

This is an elegant and simple approach to thinking about what our business model needs to be in this new world.

Do we provide a product, a service, a platform or a solution?