Thursday, 8.38pm

Sheffield, U.K.

The factory of the future will have only two employees, a man and a dog. The man will be there to feed the dog. The dog will be there to keep the man from touching the equipment. – Warren Bennis

I’ve had a few days where my routine has been knocked about a bit. In case you’ve forgotten I’ve been trying work through a book project called “Community” and I’ve found this one hard going from the start. And I wasn’t sure exactly why but I wonder if I’ve found something recently that may help explain what’s going on.

Here’s the thing. What do you think of when I talk to you about community? I think there’s a confusing mix of ideas that come up for me. There’s the memory of community, the places I grew up in and the experiences I had. There’s the reality of community now, the threads that connect me to where I live and what we do as a family. There is the online world and its strange creation of connections across space. And there’s what we imagine community to be in all these spaces and online and in the future – and it gets very difficult to figure out exactly what we’re talking about.

So I thought I’d just take a step back and look at this again – look at what exactly I’m trying to approach with this project. After all, I’m 42,000 words into something, around halfway through my stack of slips of paper that are supposed to be an outline and I feel like I have no idea what I’m talking about or how to pull it all together. But that’s ok, I’ll keep telling myself, and soldier on.

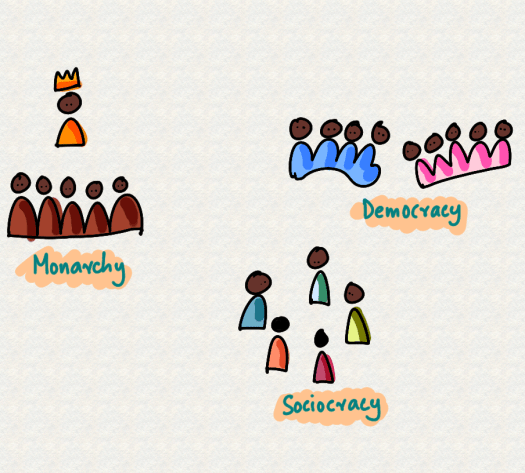

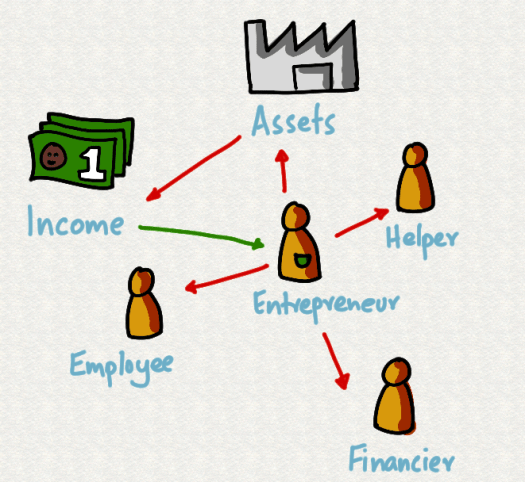

Let’s start with you and what you do. The system we live in looks something like this. You have an entrepreneur who raises money from a financier to invest in assets. The entrepreneur gets help from lots of people, from advisers to salespeople to use those assets to create revenue. The helpers get a cut of the action in commissions and the entrepreneur pays employees to work and the financier a return on the money. The government takes a cut and the entrepreneur puts what’s left in their pocket. They get paid last, but if they create value can be the ones who get paid the most. Or nothing. It depends on how things work out.

Now, which role do you have right now? Are you an employee, entrepreneur, helper or financier? And what’s going to happen to those roles in the future? Will they exist in the same way they do now or will they change dramatically, be completely different and result in a new and different kind of society?

Let’s look at one approach that’s gaining currency. In this new world robots will do all the hard work and humans will have very little to do. They can spend the time freed up to do creative and fun things but they probably won’t be paid and so you’ll need to give them a minimum income to buy food and pay rent and all that kind of thing. Now that’s not actually what the approach says – you also have the issue of ending up with two kinds of people – ones that can work and ones that can’t. Some people will be bright and clever and build the robots or do heart surgery working with robots, or they’ll do complicated manual work that robots can’t do like cleaning the insides of cars and wiping old people’s bottoms. And then there will be people with no skills who will end up fighting each other and going to jail.

The alternative view is that this is simply creative destruction and it’s always happened like this where new technology comes along and everyone’s worried about losing jobs and new ones come along and what you need to do is help the people left behind transition but eventually they do – or their kids do anyway and then life goes on until it changes dramatically again. I have some sympathy with this second approach because it’s what I see happening around me. There are some people who are doing well as the world changes around us and they seem to be predominantly people who work well with machines – whether that’s behind a desk or using a chain saw. Labour – the pure stuff of your hands and sweat is less and less useful but augmented labour, labour with an exoskeleton – now that’s still worth something.

What do I mean by that? Well, the person who does my tree and bush trimming comes along with a suit of armour and a machine, the joiner and sander have tools and extraction units – technology is everywhere and people who know how to use it do better and faster jobs and get paid to do what they do. And if you do it manually there’s still some room for you, but you will probably be paid less and let go pretty quickly if you aren’t good or don’t get on with people.

This is not new. Robert Pirsig talks about this in Zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance – about how his city friends seem somewhat afraid of technology while the hick farmers they look down on are talking about their cool new tractors and have the tools and know-how to fix something when it goes wrong.

What it comes down to then is know-how – knowing what you need to know to be able to contribute in society now and society as it changes in the future. Education is designed to turn out clerks and labourers and that’s actually ok then, as the world changes. If we have people who can program computers and people who can work with machines we still have a future filled with opportunities to do productive work. Some things change, perhaps everything changes, but I don’t see our need to do something going away. But you have to know what to do.

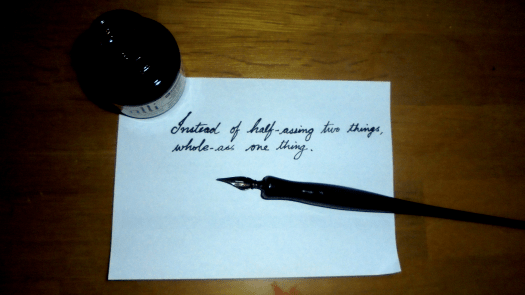

That leads to another thing – we live in a world where it is easier than ever to learn something new. We have unparalleled opportunities to discover and learn and create and do – as long as you want to do it. For example, I’ve never really learned music. I did lessons for nine years, going to a class weekly and apparently being taught how to play drums but clearly something went wrong because I didn’t learn anything. That’s 48 days I spent doing something, but what exactly?

I was walking back the other day and listening to a person talk about their history and the fact that they started learning how to play the violin at age 2. I’m never going to get that time back so what do I do? Accept that I’m never going to learn music – that it’s too late for me? That I’m obsolete?

Well, this was a long walk and what I realized was that while I’m probably too old to learn an instrument what I do know how to use is a computer. So I looked at how people use computers to create music, preferably using open source tools and came across a few articles and the idea of a tracker – something from the 90s. This is a tool where you lay out music and play it. And so I decided to have a go. Apparently the learning curve is a steep at the start but that makes it interesting and after a day of watching YouTube tutorials and messing with the system I had my first tune.

Here it is.

Not impressive at all, is it?

But here’s the thing. It’s a start. It’s me augmenting my limited physical skills with technology to do something I didn’t do when I was young, even though I had years. And now I don’t have years – just like you don’t – but we have options and resources that generations before us couldn’t even imagine existing.

So, what does the future look like?

It’s one where you can learn almost anything, from someone who is uniquely qualified, probably for free. That’s not the future really, it’s the present – it’s already here.

It’s just that people don’t quite know what they have access to sometimes, or they’re scared to try or worried about having a go.

After a few years of writing this blog that’s probably the one thing I’ve really learned. Don’t worry about what other people think. In fact most people are too busy to even look in your direction. And that lack of interest, that anonymity is good because it gives you time to practice and get better and get good and find what you want to do, whatever stage in life you’re in.

The only suggestion I have is that you start doing that as soon as possible. Because the future isn’t going to wait for you.

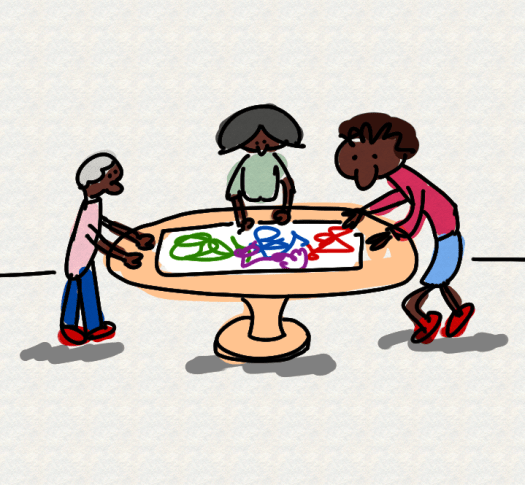

Now… I think this post is a little departure and at the end of it I think the conclusion I’m heading towards is that society will still exist, people will still come together in communities… so it’s still worth going through the elements of that I had on my list.

And the next thing I had was to look at what happens when you have splinters and factions in a community.

Let’s have a go at that next.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh