Wednesday, 8.28pm

Sheffield, U.K.

Those that know, do. Those that understand, teach. – Aristotle

Everything is a business these days. Even things like the business of health and the business of knowledge. And when there is money to be made you get things that look like what you need but are different – that somehow don’t deliver what you’re really looking for. Of course, this isn’t helped by the fact that often we don’t know what we’re looking for or need in the first place.

I feel like a cranky old person, someone who is complaining that the way other people do things is wrong. Is that because I’m envious that they’re doing it and I’m not? Is it because I think they’re wrong and I’m right? Or is it that there is something just not right about the way we make a business of everything?

Maybe it’s a cultural thing. When I first came across the idea of Pay What You Want – that seemed the kind of thing that really gave users a choice. If you felt something had value you felt the obligation to pay for it. And it probably didn’t make anyone a great deal of money but it did give them an income of some kind.

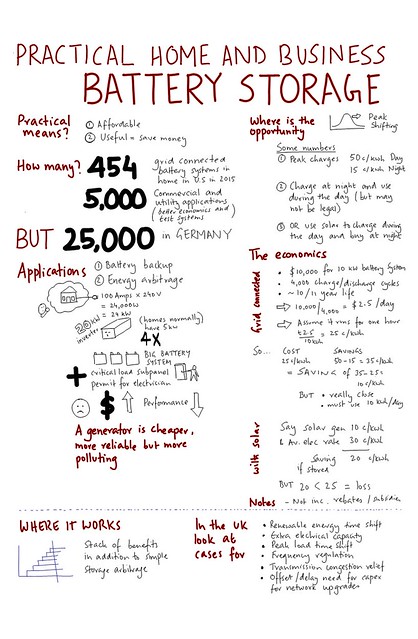

Now, of course, there are arguments that it takes money to make anything and if you don’t treat it like a business then it won’t have any value. But then again, what is a business? The bits that add value are marketing and operations, as I think Drucker said. Everything else is a cost. If you can create a customer then you’re on your way to having a business, or at least something that is value adding.

Here’s the thing. How do you tell a real “business” from something that is simply a transfer of wealth from one person to another? Warren Buffett seems to have the answer to these sorts of questions in his many letters. In one he reminds us that “Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.” In another you have a story of a family – the Gotrocks – who might more accurately be called the Hadrocks. This is because they get hooked into paying for advice on how to handle their money. It’s worth reading the full story but the key takeaway is that the more activity there is the less your return. What you want to do is make a return as efficiently as possible in whatever you do. That’s the goal.

What this means when it comes to a person trying to convince you to learn from them is that if they were so good at doing what they say they do – then why aren’t they making money doing it rather than teaching you how to do it? I remember going to one of those “free” seminars where someone talks to you about Forex trading and how they’ll teach you everything you need to know about trading and making money almost risk free. Well, if it were that easy, surely they should do it and not tell everyone else? Or is it the more likely case that they make more money from your teaching fees than they do making trades with their own money?

The reason I’m wondering about this is that I like the idea of teaching – especially because it helps me learn better. But I don’t like the idea of teaching a secret, proprietary or some made-up method that has no grounding in research or practice. I am irritated by a particular person who has started a line of courses priced in the thousands of dollars that tries to create a certification program to teach something that, from what I have read of the material, is not good. But… if I think I can do better, shouldn’t I be doing that, rather than complaining? Shouldn’t people just make up their own minds?

Anyway….

I suppose when it comes down to it, experience is the best teacher. And then when you understand what your experience has taught you, perhaps then you can actually teach others. Because I think that the best teaching happens when what’s important is what you’re teaching and what the student learns – and it stops being about the teacher at all.

In fact, that makes it very simple to decide what’s good and bad. If you go to something where the teacher is the centre of everything then you’re the product, someone who is just there to pay for a performance. If you go to something where you’re the centre of it and the teacher helps you discover and practice, then there’s a chance that you’ll learn something valuable. And that will only happen when your teacher is confident enough about what they do and have done to put away any ego and focus on helping you become better. If you find one of those kinds of teachers stick with them.

It’ll be worth it.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh