How do you make a decision about what to do next?

Which job should you choose, which option should you explore, which project should you spend time on?

These are problems we face every day, often under time pressure and with limited information.

Take, for example, one of the most important decisions you make – what job to do.

This is a decision that has a major impact on your life and carries a lot of emotional weight. You will be influenced by experiences in previous jobs and what your goals and expectations are of the future.

It is a high stakes, high emotion decision.

In a crucial decision such as this, you should be taking into account several parameters and thinking clearly and carefully about your options and what you should do.

Instead, the human brain often gets overwhelmed and focuses on one or two factors and excludes other, equally important ones.

It defaults to emotional decision making, with people making choices about how they feel about the factors that seem most important at the time.

One study, for example, found that more than half of the people surveyed left their job because of their relationship with their manager.

That single factor might have been enough to discount all the other positive factors that might have made it a better choice to continue with that job.

So how do we make better decisions when it comes to a crucial problem like choosing your next job?

One tool that can help is called a decision table.

First, identify the paramters that are important about the problem.

What are the things that you should consider when assessing the choices you have open to you?

When you are doing this, it is important to consider more than just the ones that come readily to mind. What do other people think, what does the research indicate?

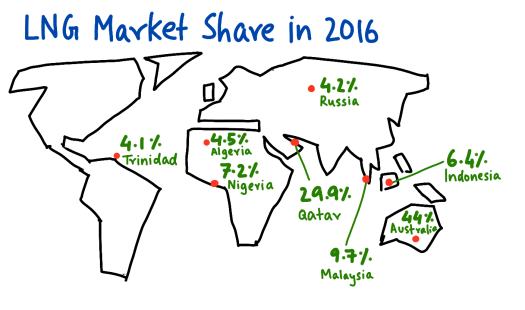

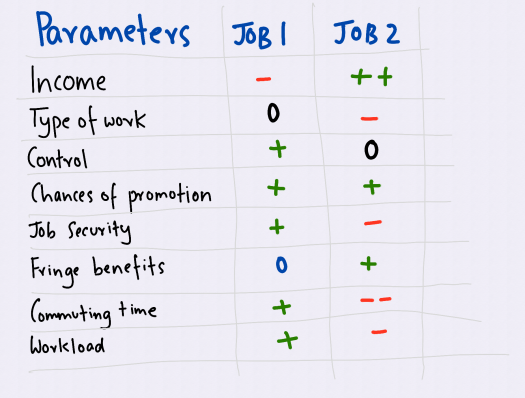

The list of parameters in the image above are from research that was carried out that identified the eight factors that were most important to the study participants when it came to job satisfaction.

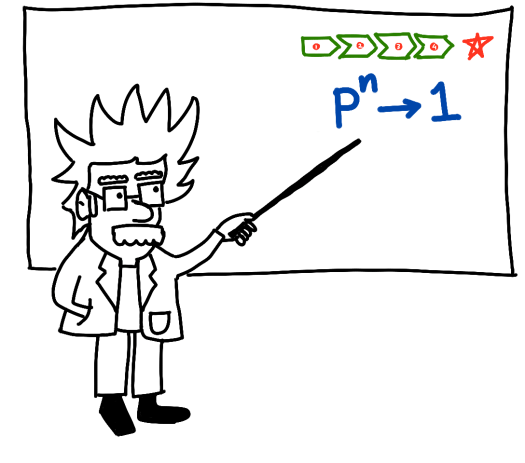

Second, assess each job option you have against the parameters.

The question to ask yourself is, “Will this job mean I am better off or worse off on this parameter”.

A simple coding system to use is to use 0 when there is no change, + when you are better off and – when you are worse off.

In addition, you could use ++ and — to indicate when an option makes you much better off or much worse off.

Just doing this exercise means that you will consider each factor in turn and assess how your life will improve or worsen under each option.

At the end of the process, you will have a table that shows you how each job compares on the parameters or measures that are important.

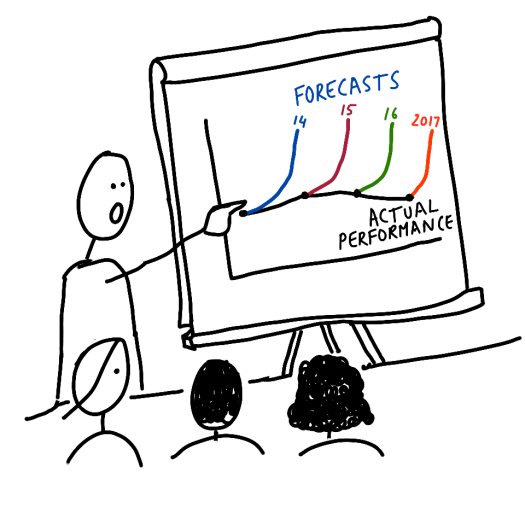

Now that you have considered all the parameters, you can figure out which ones are more important to you.

Are you, for example, prepared to take on a long commute for the prospect of much more pay?

Or would you rather have less pay and a better commute?

Are you ambitious – is getting a promotion really important? Or are you at a stage when you want a job that will pay for food while you get on with something that is important to you, like a creative pursuit?

A completed decision table will help you have that discussion with yourself or with someone else and help you consider all the factors that are important. It will lead to a more balanced decision.

It also greatly increases the chances that the decision you eventually make will actually result in better job satisfaction.

The same process can be applied to other areas. Perhaps not things like whether you should have coffee or tea, but definitely the important decisions, like where to invest, what to do, who to enter into business with.

When you have a problem that is important and where there is a high emotional component, that is the time to get out a pencil and start working on a decision table.