Sunday, 9.01pm

Sheffield, U.K.

You can’t do much carpentry with your bare hands, and you can’t do much thinking with your bare brain. – Bo Dahlbom

Today I came across a talk by Daniel Dennett for the first time, in which he introduced the quote that starts this post.

The quote resonated with me because much of my work over the last couple of years has been around trying to make sense of things – finding some kind of clarity in the messy real world that we live in.

It feels like different people have approached this in different ways over the years.

At one extreme you have approaches that are rooted in meditation and thought – the kind of thing you imagine Zen Buddhists doing.

It’s a long process of study and practice – at the end of which they achieve enlightenment – which I imagine is making a sort of peace with reality.

Although I did read a quote that said something like if anyone thinks they are enlightened, they should spend a weekend with their family.

At another extreme you have people of certain forms of science who believe that if it cannot be observed and measured it does not exist.

For them it’s about research and measurement and electrical flows and visualisations – about the detail of what’s going on in the physical world.

Now, it feels like there are many extremes as you think through the options.

For example, another extreme is the self-help guru, the person who has come up with a method that has worked for them and which they believe will work for you.

You find these everywhere, because surely if someone has achieved something then doing what they’ve done will work for you.

In Dennett’s talk he says you should install a surely alarm.

Whenever you see the word “surely” in a passage what it means is that the author hopes you’ll accept the point without questioning it.

They’re not totally sure about their point – if they were, they’d simply say that.

So, with the “surely”, they’re often trying to get something they believe to be true past you, hoping you won’t notice.

But you should – and perhaps probe more deeply into what’s going on.

Another extreme is Dennett’s own field – philosophy.

Some people believe that philosophy is the way you understand things – a rigorous way to understand what is true and false.

But really, what you need to understand is that philosophy is a form of logic, much like mathematics.

And Godel proved that even with maths, there are things you need to believe – things that can’t be proven using the system of maths you’re using.

Axioms.

What this means is that pretty much everything is rooted in a belief – and the reason you carry on believing is because nothing absurd results from thinking that way.

So, what I’m saying here is that some people believe that you have to just “get” it for yourself, others that you have to break it down scientifically, others that they have a way that’s worked for them and a few others who say this is the logical way to do things.

And then there are probably a few more ways to go.

What I’m taking from this is that reality is complex and complicated.

There are so many threads of thought, things that happen and what we think about those things happening – so many different ways we could approach the world.

What often matters is finding a way that works for us.

It’s what I’ve thought of as “models” for a while – perhaps what Peter Checkland calls a “holon” – and something that might be captured by Dennett’s concept of an “intuition pump”.

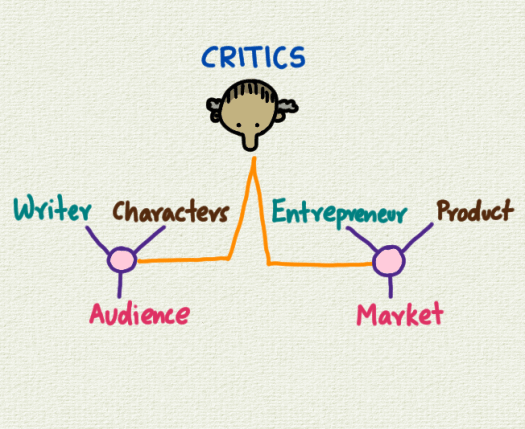

This is something that “focuses the reader’s attention on the ‘important features'” – something perhaps like I do in the model above.

Although what I’ve done is draw some circles around a random bunch of squiggles.

Still, perhaps, looking at those sections of squiggles can help us make some sense of what’s going on.

And I think that’s the point.

We’ve got to a stage in human evolution where just thinking about things isn’t enough.

There are tools that can help – and I suppose we are taught quite a few of these in school.

But many of us then forget these, or don’t go on to learn more tools, and end up trying to get through life on our bare brains alone.

What I see is that approach leads to discontent and worry and stress.

I remember, early in my career, as experiences piled up and I found it harder and harder to get what was happening.

And then I went back to university, did a management degree, and was introduced to models and ways of thinking that helped me make sense of the experiences I had had.

All of a sudden the feelings fell away – having words to describe what was going on meant that I could understand it better, and so there was no more need for feelings of doubt or inadequacy or shame.

Making sense of things matters – but there is no grand “sense” that we all share.

Instead, you have to make your own personal sense of things – but having good mental tools will help.

Some of which I have tried to use as I write this blog – the point of which really is to help me make sense of the world around me.

I hope it helps you as well.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh