Good decisions come from experience, and experience comes from bad decisions. – Rita Mae Brown

Thursday, 10.06pm

Sheffield, U.K.

Sometimes it takes me a long time to get things.

A really long time.

For example, I always thought of “u” and “w” simply as letters in the alphabet.

You know – how it goes in the song you learn with your ABCs.

It was only when I did a poor attempt at learning french that I heard the sounds “ve” and “duble ve” and realised that a “w” was actually two “u”s – a double “u”.

Maybe it was just that my kindergarten focused more on rote learning and less on making sense of the origin of language symbols.

Which also makes sense when you consider that the teachers were dealing with four year olds who were struggling with the concept of staying in one place for more than two minutes.

Anyway…

I read something on Medium that is totally obvious when you read it but that, if you’re anything like me, you might have missed until now.

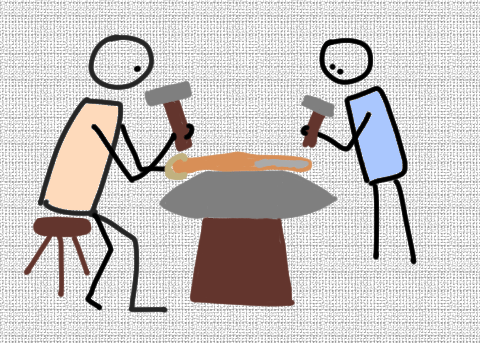

It’s by Ariel Camus and says “What makes senior developers senior is not that they know the syntax of a given language better, but that they have experience working with large and complex projects with real users and business goals.”

We all start at the bottom of a professional ladder and it’s easy to assume that those higher up are there because they are more skilled than us.

And that can sometimes be the case.

But it’s often not.

Take a lot of academic work, for example. It’s very easy to spend a lot of time carrying out research into a particular area.

The problem is that when you come out of school you find that you’re starting at the bottom in the world of work.

Having those degrees and smarts and skills doesn’t automatically propel you up the career ladder.

What gets you up is being able to show people with the power to make decisions that you’re the person they need to get a job done.

I suppose we should be careful not to confuse seniority with power.

Some people get to the top because they’re good with relationships or politics or power.

That’s not the kind of thing I’m talking about here.

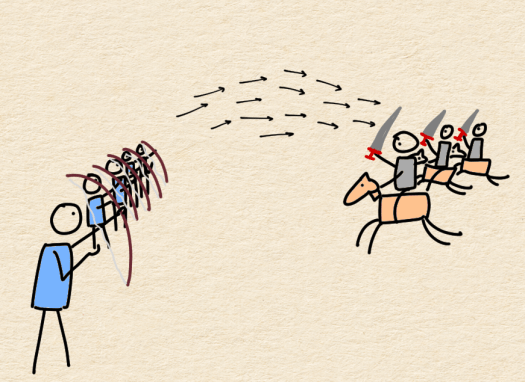

What I’m talking about is the kind of knowledge that comes from trying to solve problems.

Preferably ones that real people have. And ideally ones that are expensive to leave unsolved.

It’s obvious really. It doesn’t matter how smart your work is if no one cares. If someone does care, that’s good but you’re not going to make a living unless they care enough to pay you. And they’ll only pay you based on what you save them so the more impact you can make the more you can make.

It really comes down to the old saying about years of experience.

Have you got ten years of experience?

Or do you really have one year’s experience repeated ten times?

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh