Friday, 10.17pm

Sheffield, U.K.

There are no facts, only interpretations. – Friedrich Nietzsche

I’ve been thinking about perspectives for a while – about how we get locked into points of view without realising it.

It’s the tools that do that to us really.

For example, I’ve started using paper more again because I’m in one place a lot more.

And there are pros and cons to paper – which is why we try digital and find that it doesn’t do everything we want it to do either.

Now, the thing that happens is we find a way that works for us and start using it.

Which then complicates things when we have to work with others who use different approaches.

One way of resolving that tension is through the use of power.

For example, in one of the notes I found as I sorted out my archives was an exhortation never to let anyone use their own notebook.

If you work in an engineering firm your ideas are the property of your employer.

So, you should really keep bound notebooks, with numbered and dated pages so that if you invent something you can prove that you came up with it and own the associated intellectual property.

Well, your company does, anyway.

It’s the same thing with sales.

If your sales people go out and gather intelligence from prospects who should have that information?

The company feels it should be them.

So, a big part of organisational life is about controlling the intellectual contributions of their staff – collecting and filing it in case it’s useful later.

But really, these days what’s the point?

There are a few people out there for whom this kind of approach is justified – people who come up with patents and want a manufacturing monopoly.

For the rest of us, we deal with ideas – and ideas don’t need protection.

If I tell you an idea, I haven’t lost anything and you’ve gained something.

Many people will take the idea and run, but some people will ask you questions, want your time and pay for the things you create – those are your customers and you should focus entirely on them.

And not on anyone else.

Now, the point I’m wandering away from has to do with perspective.

You can look at the world of intellectual property in one way and have a particular point of view.

But, other people in different circumstances will have different points of view.

And you will find that there will be inevitable conflicts.

So, we need ways to switch between perspectives and take multiple points of view.

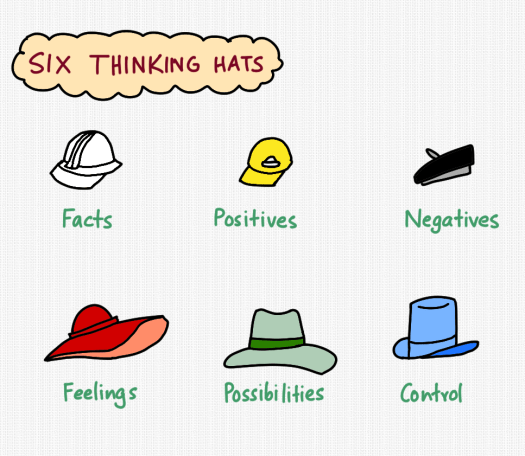

One method, an oldie but probably still a goodie, is Edward de Bono’s Six Thinking Hats.

The idea here is that you give someone the blue hat – that person is in charge of keeping things going and managing a meeting.

That person starts by asking everyone to put on white hats – they’re going to think about the facts in the situation – the hard things that we know to be true.

The hat up there is supposed to be a hard hat, by the way.

Then, you put on your yellow hat, and think about all the positives – the ways this could go well and the benefits you could get.

This hat is a backwards baseball cap, in case you’re wondering.

Hopefully the hats get easier to recognise from now on…

Then, rip the idea to shreds, talk about all the things that can go wrong.

Put on your black beret of defiance, your anti-establishment symbol and find all the ways this can fail.

Then, get the red hat on and talk about feelings, your emotions about the situation.

And then get creative with your green hat – what are all the ways you could adapt, change, innovate to make things happen.

Now, this hat process is a pretty good way to shift perspectives.

I remember doing it years ago, and thought it brought out some good ideas.

That really didn’t go anywhere after that.

That’s one issue with these kinds of facilitation methods – unless you have a “what next?” process that leads on from a session like this, you’ll have a good meeting and feel very enthusiastic, but not much gets done to change things.

But the basic idea is sound.

When you look at the same thing in a different way, you’ll spot new things, things you wouldn’t have seen with the old view.

This is why What You See Is What You Get (WYSIWYG) tools are perhaps bad for creativity.

Maybe it’s a good thing to write a first draft by hand on paper – so that your typewritten copy is a fresh perspective on the same thing.

I like doing stuff on the command line for that reason – there is a difference between what I put down and what emerges – and that is a useful shift in perspective as you go from creative to critical mode.

Like most things in life that are important – this issue of perspectives is something that is not obvious to everyone – perhaps it comes later in life after you’ve had some experience of how the real world works.

But if you ever wonder why people don’t seem to understand you or what you’re trying to say, stop for a bit.

And spend a little time trying to understand their perspective on things.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh