Households in the UK spend between 12 and 27% of their disposable income on transport, of which a third can go on the cost of fuel.

People spent, on average, £72.70 on transport in 2016 and the cost of petrol and diesel was the biggest contributing factor.

Oil prices went up and down in 2016. At the start of the year, they were low and went lower on abundant supplies, with the spot price of crude oil heading towards $25 a barrel.

In the second and third quarter of 2016, producers responded with spending and production cuts, which helped prices head back towards $50 a barrel.

By the end of the year, OPEC’s decision to curb production and stick to quotas and an agreement from other countries to reduce output sent prices towards $55 a barrel.

So, in a market where global prices can double or halve in a year, why do these increases or decreases not show up in prices at the pump?

A litre of unleaded petrol in the UK went from around 102 pence per litre to 115 pence per litre by the end of the year.

We’ve all seen that when global oil prices fall, the reductions don’t seem to show at the pump. But when they rise, the price at the pump seems to go up straight away.

Why is this?

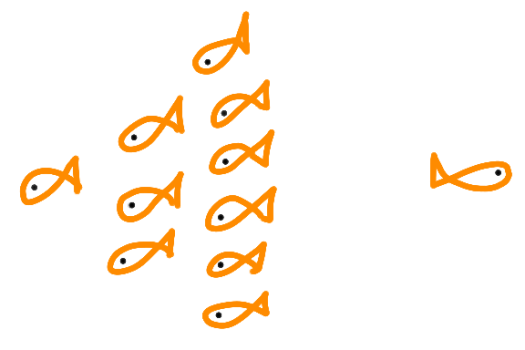

It’s not just imagination. It turns out there is a phenomenon, described in the industry as “Rockets and Feathers” that takes place.

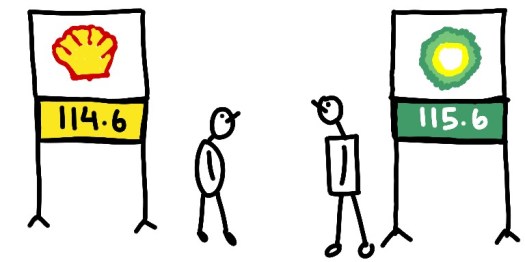

In a commodity market, where prices are posted daily for all to see, as in the domestic fuel market, retailers know what each other is charging.

If oil prices go up, one retailer can raise prices in the knowledge that others in the area will see the increase, and feel like they can increase their price as well to benefit from the increased margin.

As everyone can see the posted price, this can even act as a signal to other producers – although there is no actual collusion taking place.

On the other hand, when global prices fall, each retailer can wait for someone else to take the first step.

Again, because they can see all the prices, there is no need to drop their price until someone else does first.

So there are different incentives when prices go up compared to when they go down.

This is why price go up fast, as one retailer raises its prices, the others notice and they raise theirs as well. On the way down, everyone waits for someone else to make the first price reduction.

And so, prices rocket up and drift slowly down.