Most of us shouldn’t be doing any technical analysis.

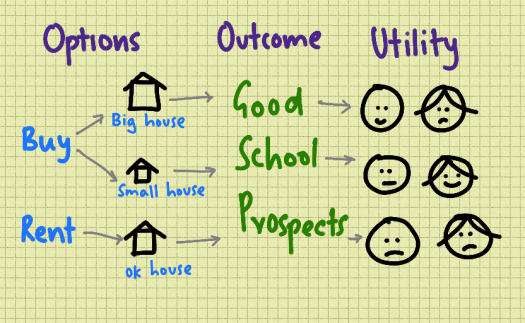

If you are an end-user – someone who actually needs a commodity and uses it in real life, then the maths of markets shouldn’t be the main thing you think about.

Instead, like in any other business, the closer your purchase price is to the cost of production, the better the deal you’re getting.

In a commodity market, like the electricity and gas markets in the UK and Europe, the best strategy is to first work out that number.

Then wait.

When the market price is close to your number – buy.

If you buy too early and the price goes doen – then buy some more and average down.

But – these opportunities only come along once in a while. In the last 15 years, there have been perhaps four occasions when the price was right and it made sense to fill your boots.

So… what do we do if we have missed those opportunities?

At that point, many people fall back on market timing – trying to get a better position by making a call on the whether the market will go up or down from where we are now.

And the tool we use is technical analysis.

The idea is that a combination of indicators can help us come to a view on where the market is headed.

The indicator to start with is the Moving Average. This is the average of a number of days and smooths out the daily variations in prices.

When a 9-day moving average crosses the 20-day moving average, it can be a signal that the market is going to change direction.

Between these, the smoother curves help us form an opinion on the trend.

In commodity markets, the Relative Strength Indicator or RSI is a popular measure.

The RSI is created by adding the number of days the market went up and dividing it by the number of days the market went down and turning it into an index from 0-100.

When the line crosses above 30, it’s a bullish signal and when it crosses below 70 it’s bearish.

Volumes traded in the market also provide an advance signal of changes.

If more people buy, it might push the price up, and as less people engage, the price might go down.

A change in volume levels can be an early sign that the market is changing its mind.

Bollinger Bands are a more complex technical indicator.

We work them out by calculating two standard deviations from a central line, usually the 20-day moving average. The theory is that prices should be within this range most of the time.

If they break out of the bands that could be a signal to buy or sell.

The challenge in energy markets is that as the number of options increases we have more of them to track and take positions on.

There are obviously many more indicators, some fiendishly complicated.

The point is that markets may be closely correlated – but that doesn’t mean just looking at one measure, like an annual contract, is enough these days to pick out a price that is undervalued.

In an ideal world, we would buy at cost-price and not need to do any technical analysis at all.

But – when we do, it’s useful to know how it’s done.