The price of bitcoin has gone up by over 16 times this year.

At the start of the year, one bitcoin traded at under $1,000. Now it is over $16,000.

What’s going on – and can it continue?

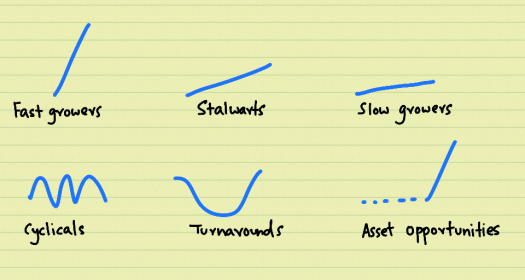

The price of bitcoin is driven, as are most things, by supply and demand.

Supply, in the case of bitcoin, is controlled by an algorithm, and new bitcoins are created by a process called mining.

In theory, the total number of bitcoins will not exceed 21 million by 2040.

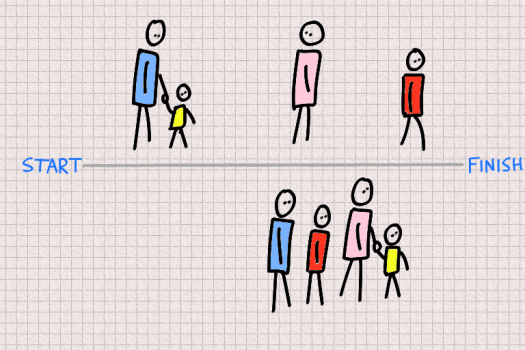

According to Bloomberg, around 1,000 people control 40% of the market for bitcoin.

The currency’s elusive founder, Satoshi Nakamoto, is believed to own around 5% of the market, or 1 million bitcoins, worth around $16 billion at current prices.

The price has been driven up by the rest of us, competing to be part of the rise in valuation that has happened over the last year.

A relatively fixed supply and voracious demand are behind the increase.

Bitcoin has no government backing it and has no intrinsic value.

Its valuation is supported purely by the belief its community of users have in it.

That is no different, really, from any other currency though – we have to believe that the country backing it will still be there in the future.

An MIT Technology Review suggests that bitcoin may be at the point where it is as powerful as a government – China’s attempts to ban it have not stopped it.

The main problem at the moment with bitcoin is its volatility and a marketplace for bitcoin futures may help to stabilize its value.

The point is that while the supply of bitcoins is fixed, the supply of crypto-currencies is unlimited – anyone can set up a new one.

And the thing that is drawing people in is not that they really want to hold bitcoins – it’s that they really want to be able to convert the rise in their bitcoins to conventional currencies like the US dollar.

That’s speculation and could be hazardous to your wallet. Or make you very wealthy.

No one really knows.