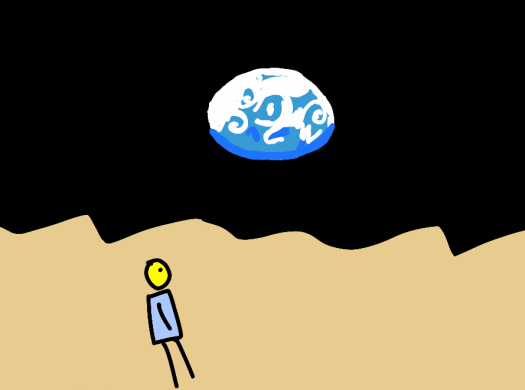

What happens to us if we see our planet from space?

The overview effect is a mind shift experienced by some astronauts when seeing the Earth firsthand from space.

They immediately get that we all live on the same small, fragile planet protected from the void by nothing more than thin air.

And the things we do to mess things up here – from conflict to resource exploitation – are simply stupid and what is needed is the united will to do something about it.

But – less than 600 people have travelled space and that probably isn’t enough to create a movement.

As a starting point, perhaps we can look at some pictures.

Benjamin Grant started a project called Daily Overview that curates stunning images of the Earth from space and our impact on it.

These images capture how we have completely taken over the planet and the scale of activity and building we carry out – from deforestation in Bolivia to iron ore mining in Australia.

A related set of images called juxtapose shows images of before and after – how Dutch tulip fields bloom or how a patch of desert turns into a refugee city.

Contrast “England’s green and pleasant land” with the Zaatari Refugee Camp in Jordan that holds refugees fleeing from conflict in Syria.

Grant was inspired by a film from the planetary collective, available on vimeo and now viewed nearly 8 million times that explores the overview effect.

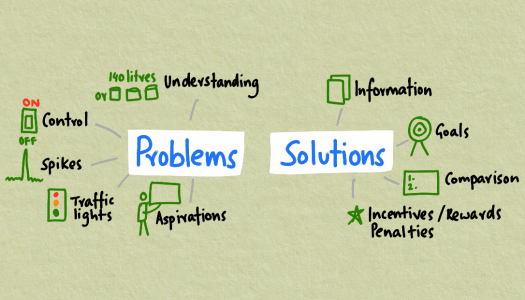

We often think that solutions to problems like climate change have to be technological – we focus on things like reducing carbon through more efficient technology or processes.

To really get people engaged we should help expand their perspective and see things from a different point of view.

And you don’t get much more different from the moon – imagine seeing an Earthrise the way the first astronauts did.

Unless you travel to the edge of the solar system.

From 6 billion kilometres away the Earth is simply a pale blue dot, the size of a pixel on a screen.

Although most of us won’t get a chance to travel into space, perhaps technologies such as virtual reality and augmented reality can help us have the same experience right here on Earth.

Maybe the technologies we have have created to escape reality can also help us protect it.