Is the quality of decisions made in organisations any better now than it was fifty years ago?

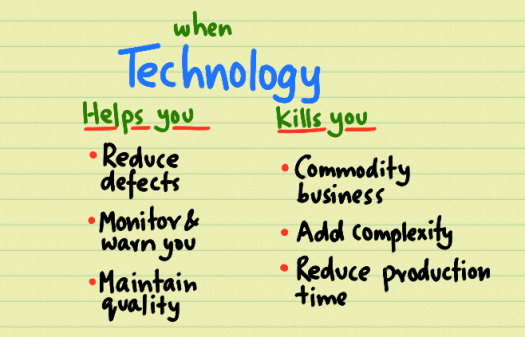

We have quicker, faster, better technology – but human nature and the way in which we think and act is still unchanged.

Which makes a working paper on Management Information Systems from 1971 by Anthony Gorry and Michal Morton an interesting read.

They use a framework for thinking about the kinds of decisions managers have to do.

Managers have to collect information and make decisions at three levels:

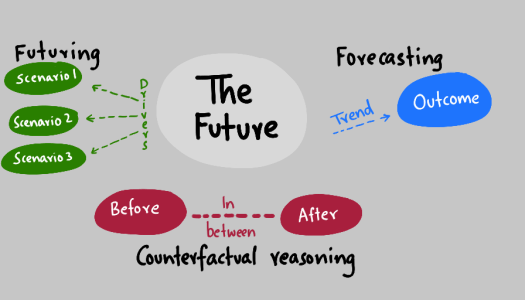

- Strategic planning: Choices about the future, done in a non-routine and often creative way.

- Management control: Getting the best out of people.

- Operational control: Making sure tasks are done effectively and efficiently.

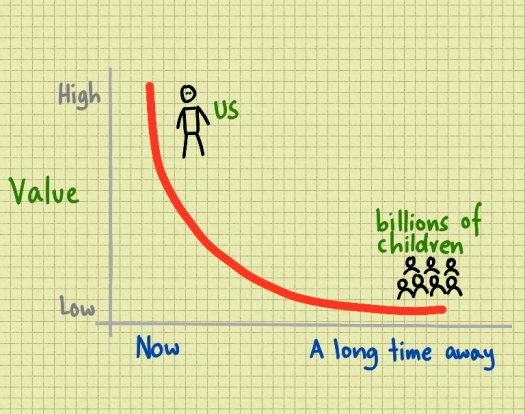

Information for strategic planning is outward looking, taking into account market conditions, regulation and what competitors are doing – but is only required when the planning activity is taking place.

Management control is about people – selecting them, keeping them and motivating them.

Operational control is inward looking, focused on what is happening right now – and the information needed to support this is obtained and looked at on a frequent basis.

So, the obvious step is to think that the better the information that we have, the better our decisions will be.

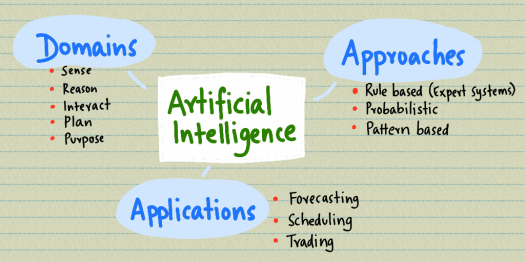

That is the one of the touted benefits of Big Data, Machine Learning and AI – if we get all the data and crunch it, the information that comes out will help us make better decisions, or make them for us.

If we think about a decision process as a black box, with information going in and decisions coming out, surely we can improve the quality of decisions at all three levels by improving the quality of information?

But there are two things we miss.

The first is that different kinds of decisions need different types of information.

Merely collecting all the data that is out there is not the answer – and we know that from nature and biology.

We often think that we see a lot of things around us. In reality, our eyes can only see in a fairly narrow band, focusing on the thing that they are pointing at.

Our brain fills in the rest of the information, so it looks to us like we are seeing a wider scene.

Instead of more data, biological systems focus on a subset of data that is important for the specific situation.

The second thing is that we can also work on improving the decision process, and this starts by recognising that the problems we apply our decision process to can be structured or unstructured.

If a problem is structured – like working out the optimal size of a batch or the most economic schedule – we can collect the relevant data, analyse it, make a decision and monitor its impact using ongoing real-time data.

Many problems however are unstructured or “wicked”.

These can’t be solved simply by throwing more data at clever algorithms.

Instead they need better decision processes – better models that can express the complexity of real world affairs.

This requires us to use human intelligence alongside machine learning and artificial intelligence.

The computers are there to support us – not think for us.

Not yet anyway.