Monday, 5.13am

Sheffield, U.K.

The first law of fighting evil is that it can’t stand the light. Even the Nazis went to extreme lengths to hide and disguise what they were doing to the Jews. When you shine the spotlight of publicity on evil it generally shrivels and dies. – Barry Clemson

Have you ever listened to a short interview on the news and been utterly dissatisfied by what happened?

The reporter asked questions that presented an opinion rather than starting a line of inquiry and the person being interviewed ignored everything and responded with the party line.

This is a game of verbal table tennis and the objective is to win points or at the very least, draw.

The interviews I like, on the other hand, tend to happen in long-form podcasts, discussions that take place over a couple of hours but, of course, we don’t all have many spare hours so we try and cram things into less time.

And that doesn’t really help, because time matters.

As do a few other things, some of which were explained by Barry Clemson and Allenna Leonard in a 1984 book on management cybernetics.

Clemson has listed the 22 laws here and I want to pick out four of them, and then two more that are relevant as we learn how to listen to others and better understand situations.

So, here goes.

The darkness principle

When you first enter a new situation, everything is dark – you know nothing about what’s going on.

As you listen to the people involved in the situation and ask questions, you start to see things, they shed a little light on what is going on.

Now, what’s clear is that you can’t know everything, understand the system completely.

You have to accept that some of it will remain in darkness, if only because you haven’t yet turned the light on that area.

Understanding this is important because it keeps you humble – you come to conclusions based on what you know so far and stay open to the possibility that new information may need you to revisit and even revise your opinions.

Of course, to shine a light as fully as possible, you must be willing to take your time.

Relaxation time

When you disturb a system – like throwing a pebble into a pond or brushing against a spider web – you set off vibrations, oscillations, waves.

These take time to settle.

You can’t force this, it follows its own schedule, its own timing sequence.

You can see this with children – if they’re in the middle of doing something and you want them to do something else how do you begin?

Perhaps you go in and tell them to stop what they’re doing immediately.

If they’re having fun you’ll get an immediate response, a negative, angry one.

How many of us have the patience to let the child finish before interrupting and escalating the situation?

Has that ever made things better?

If you want to stabilize a system what you need to realize is that the time that it takes for the system to relax has to be less than the average time between disturbing events.

In other words, wait till the child has finished and then start to say your piece.

It takes longer in the short term but if you interrupt before the child has finished and is relaxed, is ready to hear you, then you’ll simply push them again and they’ll stay angry and upset for longer – for the long term.

It’s the same when you’re interviewing someone and trying to explore an area – take your time, let the person talk about things until they’re done, until they’re tailing off or repeating themselves and then move on – give them time to answer before you disturb the situation with your next question.

Because what you’re trying to do is understand as much as you can or, at the very least, enough.

Requisite variety

How do you know when enough is enough?

That’s where requisite variety comes in.

Imagine you’re trying to pick up a stretcher with a person on it.

There are four handles.

Can you carry the person safely if you pick up only two?

How about three?

If you don’t get all four the stretcher is unbalanced and you could drop and hurt the patient.

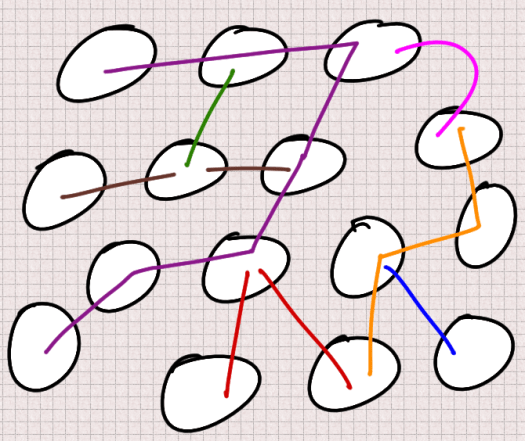

Now imagine a more complex shape, one like the image above perhaps.

If this shape were a board, where would you hold it to lift it and stop whatever is on the board rolling off?

Holding only a few won’t do – you have to pick it up on all the points that matter, the ones that affect the balance and stability of the whole.

You won’t know what these areas are – the ones that matter – until you come across them as you explore the darkness and you will only find them all if you give yourself time – time to as questions and follow trails and discover them in the darkness.

But still, how will you know that you’ve got it all?

Multiple perspectives

That’s where you need to talk to more than one person.

As you carry out an exploration with more people involved in the situation you start to see things from more than one point of view.

And what then matters is how consistent the models you are coming up with are with these points of view, are you able to see commonalities or not?

Or perhaps the same thing can be expressed in more than one way – and those ways can be incompatible because of underlying fundamental differences in how people see the world.

And that’s ok – that’s what happens in the real world.

People disagree on things.

What matters is what happens next.

Surface and hidden meaning

This principle is not one of the 22 articulated by Clemson but it comes out in the quote from him above.

As I explored his website I came across his autobiographical fragment on the Mississippi Freedom Summer, the summer of 1964.

It’s harrowing reading, bravery, following a story of non-violent action in a society that had practiced violence against others for a century without fear of reprisal.

And it tells you a bit about surface and hidden meaning.

On the surface, you have the overt display of power, a police force that has sticks and horses and believes that one part of humanity is worth less, deserves less than another.

And that police force is drawn from that part of humanity which benefits from oppressing the other.

But what we have learned over time is that no police force can control a citizenry unless the citizens agree to work with the police.

Unless there is an overwhelming, unchecked abuse of power – which we also see, of course, in many parts of the world.

But, in the world Clemson is describing, you see what’s happening in a section where this power, this control, this superiority that one race seek to display and show on the surface also conceals fear and anxiety.

There’s an incident with an old farmer who seems “hysterically afraid” – worried that Clemson and his friends are “communist agitators here to destroy the Mississippi way of life.”

That’s not very different from now.

Every government is afraid – so afraid that they have to respond to or crack down on the light.

Whether it’s the developing nations, India or China with the challenges of their borders and minority populations or rich nations like the US and the countries of Europe, we live in a world where we cannot trust what’s on the surface because there is too much leaking out about the murky depths underneath.

Each of us has to choose how we act, whether we stand up publicly for the things we believe in or if we make better choices, through what we buy and do to reward those who do better.

It’s complicated and difficult so you need to have ways of understanding what you are really trying to do.

Bi Polar Constructs

In my last post I wrote about nodes and connections, concepts and links that you explore and that works pretty well most of the time.

The one refinement I have come across is George Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory which Eden and Ackermann talk about in their work on strategy and SODA – Strategic options development and analysis.

And this is the idea that what people think – their theories of how things work – are built from constructs.

Constructs can often lie on a range, they are similar ideas, but on either end of two poles, two opposites ways of being.

For example, take societies.

All societies are similar in that they are groups of people but you can have a racist society at one extreme and a multi-cultural one at the other.

No society is entirely one or the other of these, the sum total of the approaches and views of the people in that society will lie somewhere in between the two extremes.

And where they are leads to other points, where the construct is different from or leads to another point.

Like a multi cultural society faced by terrorist activity or a racist society where the oppressed section of that society decide they don’t really want to be oppressed any longer.

Now, of course, there aren’t simple solutions and it takes time to sort things out and understand what is going on and come to a compromise.

And the changes that happen on the way may not be for the better.

But they could… if you took the time to listen and understand.

Making sense of it all

If you were able to make sense of it all.

In the next couple of posts I’m going to explore two particular methods, one a top-down approach and the other a bottom-up one to see if they can help

Until then,

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh