Tuesday, 7.58pm

Sheffield, U.K.

Haters never win. I just think that’s true about life, because negative energy always costs in the end. – Tom Hiddleston

Many years ago I spoke with a girl who seemed to see things other people didn’t.

Like energy – she said some people sucked energy from you, while other people didn’t.

I didn’t quite know what to make of this at the time and, to some extent, I still don’t.

Do people who need to talk things through with you – the ones who spend hours going through their experiences fall into this category of energy vampires?

Or is it a more insidious thing – are there people who are relentlessly negative? The ones who see the dark side everywhere, the possibilities for failure and who seem to take a perverse delight in seeing others stumble and fall?

There is a line, somewhere between normal conversation and the need to unload one’s feelings, and this other place.

At the extreme is the feeling you might get if you were one of the victims in the picture above – a loose adaptation of a scene from a well-known film still in cinemas at the moment.

I remember being relieved that the girl said I wasn’t in the energy vampire camp – but then I’m not sure that’s a good thing.

For example, I think that my writing is relatively balanced, relatively thoughtful.

It lacks the passion and angst, however, of a more driven person – it lacks the anger and drive of someone who wants to take radical action to change the world around them.

You will know people personally or have watched them – these larger than life people who fill rooms and screens, simply bursting with energy.

They can be glorified or vilified.

The press, in particular, loves the story of a person rising up and then take equal delight in pulling them down – it’s the action and angst that matters not the person.

But there’s a dark side to dynamism, isn’t there?

The same energy that one person harnesses to create a movement and positive change is used by others to create a cult and harmful change.

An uncompromising quest for the good can result in something like the inquisition – where you deal harshly with people who don’t meet your standards of what good looks like.

And negativity is not always bad, is it?

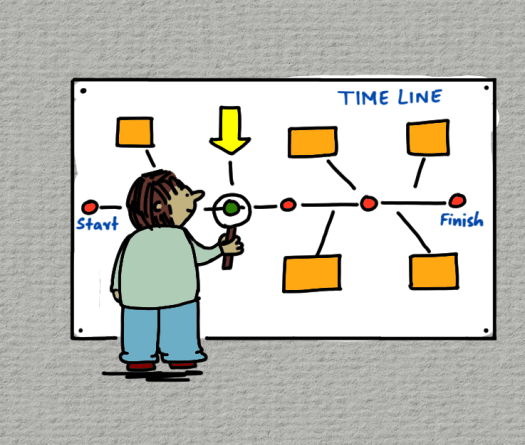

I’m often see conversations where people talk about what to do – what strategy to take.

And one school of thought is to say that no idea is bad – and you can’t win if you aren’t in the game.

But sometimes you know why a particular idea won’t work – should you stay quiet?

Or perhaps you should just say no to everything unless it’s in your sweet spot – you only swing for those shots that you have a good chance of hitting.

Is that being negative or just pragmatic?

And if the game is baseball, something you’ve never played – surely you’d be better off not trying to play and work on a sport you do know instead?

What all this teaches us, I think, is that people lie on a spectrum – from frenzied optimism to relentless pessimism.

One might say that the first thing to achieve is balance – a dynamic equilibrium between the negative and positive – so that you are unaffected by the forces on either side.

That means you don’t rush to criticise but that you also don’t rush in without questioning.

You might also want to spend less time with negative people who do suck the job from your life – but also be wary of charismatic types that draw you into their web of magic and euphoria.

Because when you’re balanced you can choose what to say and when to say it and how to act – you can make choices about how you want to be.

And surely when you have that ability – that energy – you’re going to choose to be positive and optimistic.

Aren’t you?

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh