Tuesday, 8.24pm

Sheffield, U.K.

Looking not to any one time, but to all time, if my theory be true, numberless intermediate varieties, linking most closely all the species of the same group together, must assuredly have existed; but the very process of natural selection constantly tends, as has been so often remarked, to exterminate the parent forms and the intermediate links. Consequently evidence of their former existence could be found only amongst fossil remains. – Charles Darwin

In one of David Attenborough’s programmes there is an arresting scene of two bulls, a challenger and an old veteran, going head to head.

Weighing over half a ton each, their foreheads crash together, again and again.

The challenger seems to be winning until the veteran gets broadside and drives him away.

It’s the kind of clash you remember, that sticks in your mind – because of the beauty and majesty of these animals and the seeming pointlessness of their way of setting a dispute.

But then you have to ask yourself, what alternatives do you have?

In a post on Ben Orlin’s very funny Math With Bad Drawings blog he explains the Intermediate Value Theorem as effectively saying that if at one time you were three feet tall and then at a later time you were five, then at some time in between you must have been four feet tall.

Now, what this means for you and me is that evolution and maths are telling us that what we see is not all there is.

Let me explain.

If you have a job right now, in order to start that job you signed a contract.

A contract that sets out the rights and obligations between you and your employer.

Maybe it’s a very restrictive one, where they own everything you make, even what you come up with while you’re dreaming.

Maybe it’s one where they can fire you at any time.

Or maybe there isn’t one at all – it’s cash in hand, or sometimes it’s not.

Or it’s a loose contract setting out what you will do for this employer but leaving room for you to work for other as well.

Those of us that aren’t lawyers tend to look at contracts as perfect documents, set in stone – while to lawyers they might simply be a set of statements, often imperfect, and something to argue over and settle after they’ve been paid.

An approach to management might have evolved along similar lines, from forced labour to a postmodern network of capabilities – each approach fitting into a particular niche, surviving, evolving, dying.

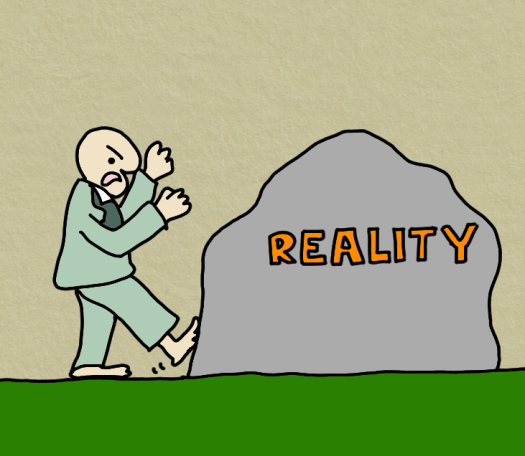

What’s obvious is what is in front of you – the end products of all those small changes, those intermediate states.

We see them as they are now – bulls, markets, societies, economies, theories – and wonder how they ever got so big and complex – surely it cannot have been by chance?

There must have been a guiding hand, a creator, someone omnipotent?

But somehow, the more plausible explanation is that these things just happened over time.

And they took time.

Which human beings don’t like – I saw a post where Paul Graham quoted some as always asking if you think something will take ten years ask yourself how you will do it in six months.

Maybe some things can be addressed that way.

Others can’t.

You can’t make a baby in one month by getting nine women pregnant, for example.

If you want to become good at something – playing music, writing, programming, managing, science, learning a language, assimilating into a society – it’s hard to shortcut those 10,000 hours or 10 years that you usually need.

But most of that applies to things that you want to do – like those bulls who want to protect their territory – or take over another one’s patch.

For human beings we have the advantage of being able to consider what to do.

We can see how those bulls resolve their differences and understand that it involves pain and a lingering headache.

And we can choose to do things differently – change the things we don’t like.

As long as we don’t get fooled into thinking that change is not possible – that the way things are is the way they have to be.

Because you can make a difference.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh