I’m a little confused about the jobs market at the moment.

I’m a little out of touch. But when I was starting my career it was the down bit of the dot-com bust.

I sent out hundreds of letters and got no response. It didn’t feel like there were jobs out there, at least not any that I could get.

But it seemed like it was a fair shot – if you kept trying you’d get something.

I’m not sure that’s the case now.

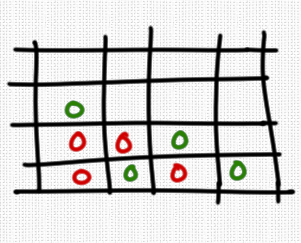

I keep hearing and seeing that people apply for a thousand jobs and hear nothing.

Okay – first, you can’t thoughtfully apply for that many jobs – it’s pretty much spam.

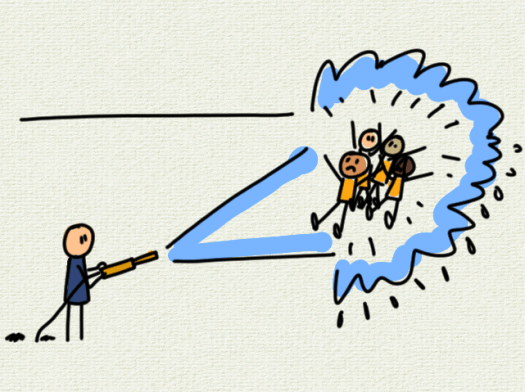

And on the other hand, recruitment managers must be overwhelmed by applications, and there’s got to be businesses set up just to maximise applications and play a numbers game.

So, the standard apply and be judged fairly system must be broken.

Which means the people getting the jobs, the opportunities, must be getting them through connections. Through knowing someone that can cut through the mess.

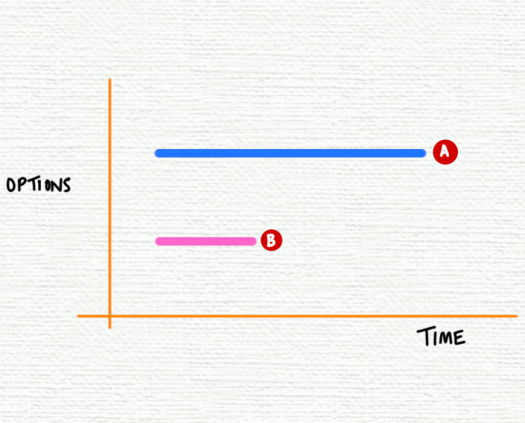

Technological solutions are making it easier for the haves to keep what they have rather than creating a level playing field.

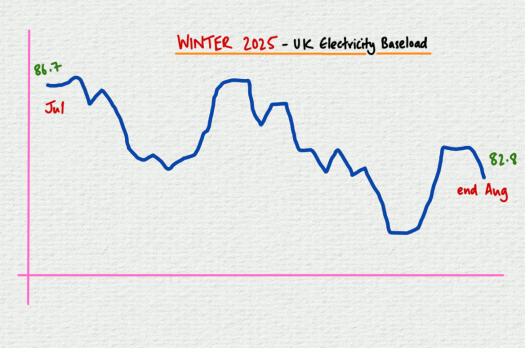

Of course, this is a pessimistic zero sum view.

If technology destroys the existing job market something new will come up.

The people succeeding are the ones using unconventional ways to get ahead – building portfolio careers from the age of 16, leaning into new technology.

There are people creating new careers that didn’t exist a year ago. New business models that are being floated and tested.

What would you tell your kids now? Do you think the university -> job -> pension route is now done for?