Linus Pauling, the only person to win two unshared Nobel prizes said, If you want to have good ideas you must have many ideas. Most of them will be wrong, and what you have to learn is which ones to throw away.

In the book A Technique for Producing Ideas, first published in 1939 by James Webb Young, the author says that there are two principles to recognise about an idea:

- An idea is a new combination of old elements.

- You need to be able to see relationships to be able to combine old elements into new combinations.

He suggests a five step technique to generate ideas: gather raw material, absorb and turn over material in your mind, step away from the whole thing and take a break – go to sleep if you can or watch a film, wait for the “Eureaka” moment when the idea will appear and finally expose it to the world – to criticism and comment so you can shape it into something practical and useful.

But how do you know if an idea is good?

Sometimes you just do – that’s what the “Eureka” moment is all about, and by putting into the world you will validate the idea and get feedback, so you increase the probability that the idea you have is a good one.

On the other hand, there are a few more criteria that are useful.

Paul Graham, in quite a long essay about how to get startup ideas, reminds us that instead of searching for ideas, look for problems.

If there is a problem – something that you want solving yourself, a solution that you could build yourself and something that other people haven’t quite realized is worth doing, then you might be on the verge of a good idea.

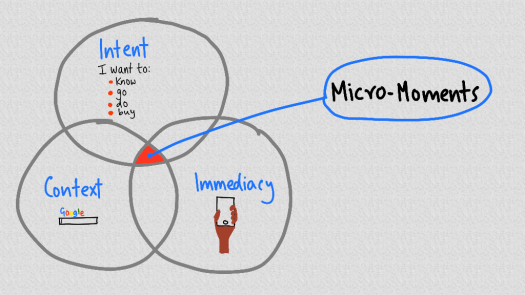

The missing piece from Webb’s model, as you can see in the picture, is that there is a person stood there, collecting the elements and working out the relationships between them.

The nature of the person is very important, but just by focusing on the idea, one might completely forget that individual stood behind the idea.

What kind of person comes up with good ideas?

Adapting Graham’s adaptation of Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance one might write:

You want to know how to have a good idea? It’s easy. Make yourself the kind of person that has good ideas and then just think naturally.

If you are already at the leading edge of a field – if you live and breathe a particular industry – then you have a better change of having good, relevant ideas.

If your mind is prepared, already aware of the issues and problems that are relevant, when a good idea pops up, you will be ready to see it and work with it.

Even better, if you have the ability to build it, code it or write it, then you’ll have a mock-up that you can show people and test whether they feel the same way about your idea and more importantly, whether they will hand over some money for it.

Finally – the real opportunity is things that other people find boring, unsexy and tiresome. That’s the pain people want taken away and are willing to pay for.

As they say in Yorkshire, where there’s muck there’s brass.