In the last few months of the year teams around the country are looking at the year ahead, setting budgets and targets and trying to work out what do do and where they should focus their time and energy.

Should you focus on where you want to go – your goals and the end result?

Do you need to know where you are going so that you know when you are there?

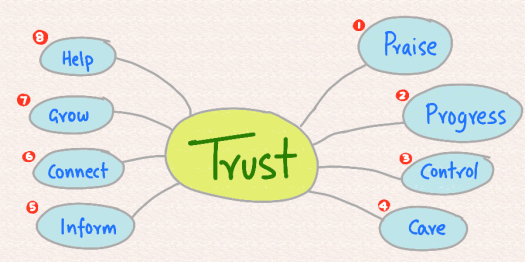

Will having the right vision and mission statement and doing lots of motivating, team building activity help you succeed?

Is getting the right people on the bus the secret?

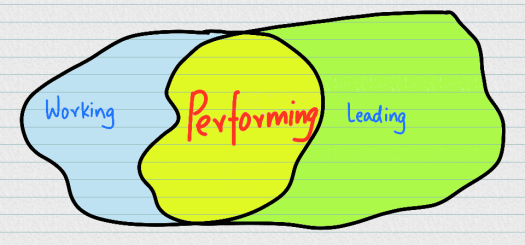

One way to see through the euphoric fog of motivational management is to consider what makes you special.

What is it that is distinctive about your business – the qualities and attributes that mean you will do better than others in your space?

John Kay, a leading economist, came up with the concept of distinctive capabilities in the 1990s.

He argued that distinctive capabilities are what you have, not what you would like to have, or hope you have.

You might start with a number of capabilities when analysing what is distinctive about you. Are you cheaper than the competition? Do you have smarter people? Is your reputation better?

Key said that there were only a few types of distinctive capability – and they stemmed from how innovative you were, how you structured yourself and what people thought about you.

He termed these innovation, architecture and reputation.

So, what do distinctive capabilities such as these have in common? How can you score them and see whether you should focus on them or not?

There are four questions to ask yourself. Is what you do:

- Hard to make and build? Does it take a long time or is it difficult to get the ability to build and maintain your capability?

- Hard to do? Is it possible to turn your activities into a recipe – something that can be recreated or adapted elsewhere?

- Hard to copy? Is what you do protected – either by laws or by its nature – a trade secret for example. Can it not be replicated easily.

- Hard to buy? Is it possible to buy what you do on the open market or is it something unique to you?

If what you do is impossible for others to make, do, copy or buy from anyone other than you then congratulations – you are on your way to a monopoly.

For most organisations, however, you will be somewhere on a range.

A strategy that works will focus on those capabilities that fall on the right hand side of the range when answering those four questions.

Whether you looking at yourself as an individual, a business unit or a business group, the chances are that you will get better returns by building on the distinctive capabilities you already have, rather than what you want.