Imagine you’re the boss. Or, you ARE the boss. What does your day look like?

You get all the crap that no one else can handle. President Obama said that by the time something reached his desk it’s really hard. Because the easy things mean someone else can make a decision and get it done.

So… what is your natural way to deal with problems – to get your people to do their jobs? And is what you are doing working?

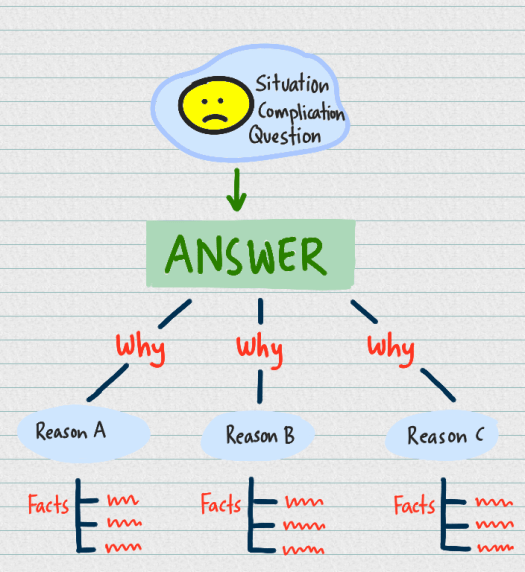

The way most people start with such a problem is to come up with a plan – or ask for one.

A plan helps us to set out a series of steps that people can follow. We can give them tasks and show them how what they do makes its way to the next person and what happens next.

In theory, as long as each person follows the plan, we’ll get from where we are to where we want to be.

Except it rarely works out that way.

If you have watched how leaders operate they often seem to go about a plan backwards.

That is, they start from where they are and then show how they always planned to get there.

Which a bit like shooting an arrow and then drawing a bullseye and target around where it lands.

So, some people say planning doesn’t work – what leaders need is a compass.

They need to make it clear where north is – with what they say and how they behave.

Then, in theory, everyone will know what the goal is, and work out what they should do to navigate in that direction.

If everyone does that, then we’ll end up in the right place.

So, how does that work?

Well – that’s the way the US military operates – and it does pretty well at it. In the 90/91 Gulf War, for example, once the ground war started they routed Iraqi forces in three days.

But – this is hard to do. And it’s hard because people in most situations don’t have to deal with life or death choices.

Instead, they have to deal with whether the builders are here or the copy is through legal or whatever else.

And so it’s hard for them to relate their day to day with the big mission – whatever the leader says or does.

The last way to look at this then, which almost no one does, is to have a model.

The theory behind this is here but, in essence, a model is something that helps us to learn what is happening in real life.

Let’s say you do something great – achieve a sale, for example. If you list out the steps you followed – what you are doing is telling a story.

It may be a great story – but it’s a story nonetheless.

For it to be a method, you need to have explained what is in your mind before the achievement. Creating a model is one way of doing this.

A model could be like a plan – a set of connected activities. What makes it more than a plan is when you use it to learn about the people involved in the situation.

The best plans can be waylaid by problems of culture or politics.

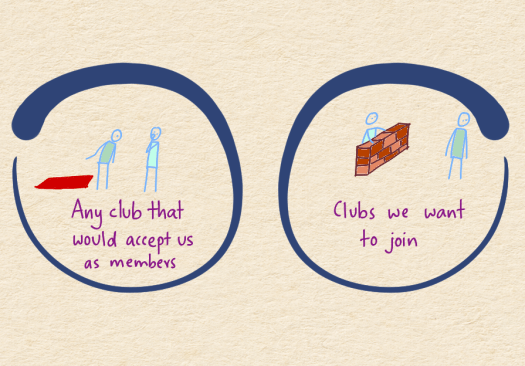

Plans and Compasses assume that people will follow a plan or navigate in the right direction.

In reality, people will do what they think is best, and that is not the same thing.

What’s the point here?

These three ways of looking at things are invisible to most leaders – they are too busy doing their job. They don’t have the time to think about how they are thinking.

Even a President, it seems, has to remind himself that he’s not going to get everything right and hopefully things will work out if you’re moving in the right trajectory.