There is no “simple button” or “magic bullet”. There is work. And there is continual improvement.

I learned something early in my career that stuck with me.

I could build technology. I’d studied, practised, was familiar with a range of tools, and could create something that worked well for me.

Reliably. Predictably.

Then, when I gave it to someone else, they always broke it in new and interesting ways that I hadn’t considered.

Some people think of this as a problem with humans – and some technologists work very hard to remove this irritant from their workflows.

But that’s a mistake. The people at an organisation are the ones that buy your product, that engage with it, that need it to make their work lives easier, that promote you if you make that happen.

So I learned to build for users, rather than just building for myself.

And this starts by understanding that your prospect is in an existing, probably complicated situation.

In that situation, they usually have an existing, probably complicated set of issues they consider problematic.

You can’t rock up and offer your nice, packaged brick of a solution to fill their jagged and misshapen issues.

It’s not going to work. Maybe you’re so great at selling that they buy it. The disappointment comes later.

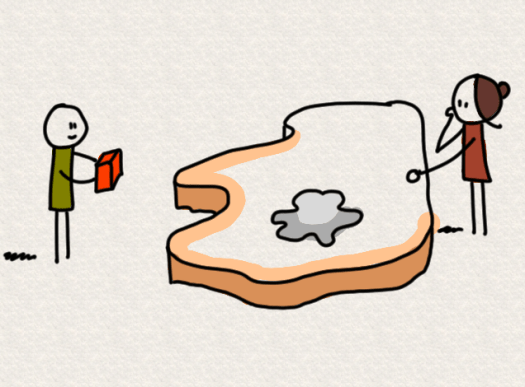

The only way is to change our approach.

We need to shape our solutions to fit our client’s problematic situation.

And then constantly work with them to improve and make it better.