The question of who owns the IP produced by generative AI will have a huge impact on productivity.

The rules have been fairly straightforward for a while – don’t copy someone else’s work.

But how does this this work when an LLM generates work for you that its remixed based on other people’s work?

It looks like the platforms pass that concern over to you.

You start the process with a prompt – which you have written, so you own.

The output is yours, depending on the license terms of the AI tool you’re using. Some seem to want to hold on to the IP, so that’s not entirely straightforward.

But the output can also be a copy of someone else’s copyrighted content.

This is most obvious when you create a character that looks exactly like a commercial one, but it also applies to code, which might be harder to spot.

There is a danger zone where you prompt an AI and get output that you then use in a commercial product without checking if it infringes anything.

This leads to a few scenarios.

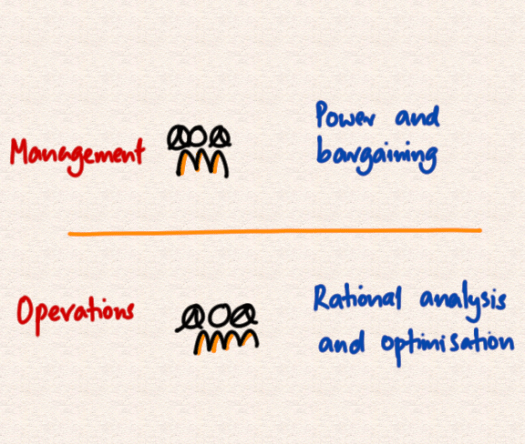

First, you need humans to check the work, so your productivity is limited to the ability of people to process and check what’s going on. You get a boost, but it’s small.

Second, the checking process gets automated and tools can give you output that has been checked against everything else and guaranteed to be original.

Third, existing protections are swept away and you can do what you like.

Fourth, the whole thing is like smoking. It feels good, you do it for a while, then find out that it rots your thinking and we start to move away from it as a society.

Five, the hype fades and we move onto the next thing.

Six, none of the negatives happen and the industry sorts out the issues and we become incredibly productive.

There are probably more scenarios you can think of.