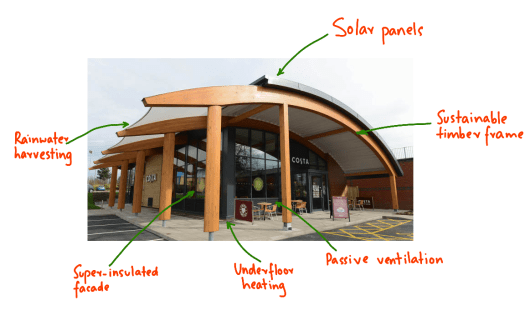

In 2015 Whitbread, the parent company of Costa Coffee, announced that they had built the first zero energy coffee shop in the UK.

In an example of how constraints help create innovation, the building has a number of features that help it reach the ‘zero energy’ standard including:

- A frame made from sustainable wood rather than steel

- Solar panels

- Capturing and using rainwater

- Lots of insulation to keep heating and cooling needs low

- Use of natural or passive ventilation

- Underfloor heating

Two of the three things on that list, solar panels and rainwater harvesting systems can be added to existing buildings.

The others involve more work and disruption – insulation, changing heating systems and installing passive ventilation can’t be done without getting in the way for some time.

And changing the frame just isn’t an option for most buildings.

The amount of energy lost because a building structure is inefficient can be considerable.

These parts of a building also have a long life cycle and may only be replaced or upgraded in some cases after more than 60 years.

Organisations that look at the life-cycle cost of their buildings may find that the long-term benefits of investing in more energy efficient design now can create huge savings over time.

But they are also fighting the short-term needs of their organisations to conserve cash and limit budgets.

So, will things be better in the future?

It is easy to predict a future full of super-efficient buildings such as Costa Coffee’s, a de-carbonised transport system and zero-carbon development.

The problem is that there are many possible futures. Which one is most likely?

A good way to predict the future is to ask what you have done so far.

In other words, instead of asking “What are you going to do to become more energy-efficient”, you ask, “What have you done so far to become more energy-efficient”.

For the vast majority of people and organisations, the answer is going to be “not much”.

And for a futurist, that suggests that in the future, people will still not do very much.

A key reason for this is that the costs of investing in projects like Costa Coffee’s needs resources now and the benefits come later.

As human beings, we are built to overvalue the present and discount the future, and this naturally leads to inaction and apathy when it comes to looking at such projects.

This is why regulation and government action in this space is so important to spur innovation and creativity.

So, while in many areas we need the government to get out of way of business, building standards is one where we may need more intervention and not less to create a low energy future.