Sunday, 5.20am

Sheffield, U.K.

And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom. – Anais Nin

We’re working through the second act of the Getting Started book project.

This is the last of three techniques to help explore the past and get some perspective on what you have experienced so far.

The first technique, lifelines, let you see the sweep and trend of what’s happened.

The second, defining experiences, asked you to pick out key events that have made you who you are.

And this technique, stages of growth, will ask you to take a hard look at the development of your career to date.

What stage of your career are you in?

This is not, as I have explained elsewhere, a book that promises shortcuts.

Transformation takes time and you should think in terms of decades, not weeks or months or years.

If something is easy to do then it’s as easy for someone else to do – it gives you no competitive edge, no protection, no defensive moat.

Those things come with time, with accumulating experience and creating artefacts and building proof.

And over a period of time, your own career will have developed.

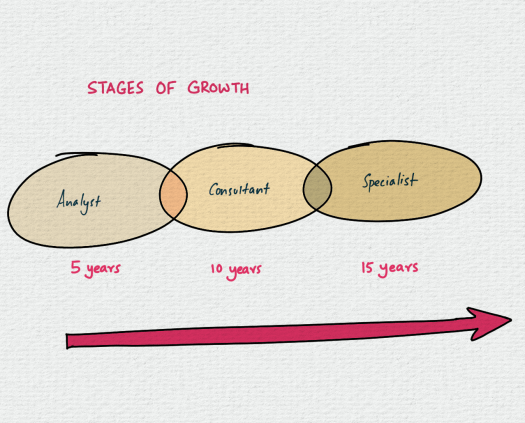

For example, let’s look at a typical knowledge worker’s career over a span of fifteen years..

The first five years are spent in learning about the field and doing analytical work on a customer’s account.

These tasks include carrying out research, documenting findings, creating analyses, creating presentations, dealing with queries and handling administration.

Most of the time you do what you’re told to do and, if you’re lucky, you get the chance to improve systems and processes and demonstrate your competence.

Over the next five years you might progress into the role of a consultant.

You now have the experience and understanding of workflows and how things are done.

Instead of having to be told what to do you can start having conversations about what needs to be done – moving from an task focus to thinking in terms of outcomes.

As a consultant, your focus is on delivering what the client needs, not completing a particular task – and the better you are at understanding their objectives and marshalling resources to deliver what is needed the more likely you are to get given responsibility and oversight.

Then, in the next five years you start to move into the role of a specialist, someone who is an expert in a particular area.

You may have your own team or operate with few resources and bring in others when needed – but you become the “go to” person when there is something that needs to be done related to your field of expertise.

Most people should be able to see themselves somewhere on this continuum, as they look back on their careers.

You can get started at any point

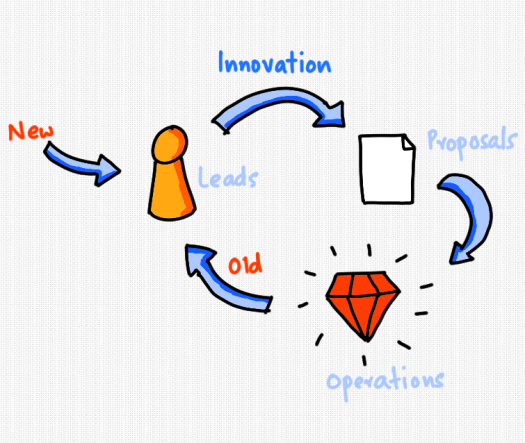

You can start a new project at any time in this timeline – but the way you think about it will be heavily influenced by what you know at the time.

Early in your career you will focus on the tasks you can help with – the specific skills you bring to the project.

The kind of business you may gravitate towards will be a freelancing structure working on a project basis.

Later in your career you will have a better understanding of the landscape and how what you do fits into what the customer does.

This gives you the ability to range more widely, creating value where you think you can.

Still later in your career you will focus on specific value creation, preferably as high as possible, to justify using your experience and higher costs.

But these will be dynamic times, filled with tension and difficult choices.

Early in your career you have less to offer but more flexibility and the ability to learn and change.

Later in your career you have more to offer but may also be getting more rigid in your thinking, less open to change, both professionally and personally.

It’s important to be clear sighted about where you are right now – because there is much still left to do.

Complete the model

Draw this model out for yourself, starting with three overlapping ellipses and adding as many as you need.

Work through your career and label the stages you think you’ve been through – use words that capture the roles and expertise you’ve developed over time.

Try and separate the stages so that they are clear in terms of growth, not title.

Going from a junior analyst to an analyst to a senior analyst may simply mean that you’ve become more competent at doing the same tasks.

Moving from being focused on getting a task done to being focused on what the client needs doing is a significant growth step in any career.

It the first step in moving from being self-centered to being customer-centered.

Getting Started

The important thing to remember the fact that you can get started on a new project at any time – but keep in mind that the next stage is likely to take another five years, regardless of which stage you’re in when you start.

Especially when what you’re trying to do is start a business or create a step change in your career.

That’s because in addition to doing what you do you need to learn how to sell what you do.

And that requires some deep thinking about the way in which you’ve changed people’s lives, which we’ll get into in the next post.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh