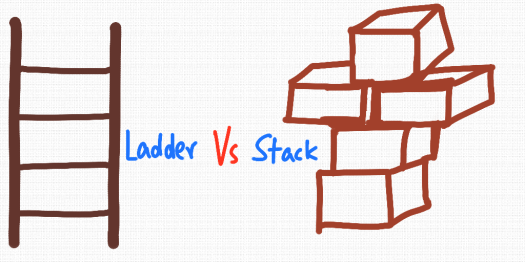

One way to think of change is like a ladder.

We move from rung to rung, stepping off the old one and committing to a new one.

For example, we used to burn firewood for cooking, and still do in some places. Then we moved to transition fuels, such as coal or kerosene. Then we might use cleaner fuels, such as electricity or natural gas.

This kind of transition seems straightforward, one way (upwards) and natural. You move from one choice to another and eventually stop doing the things at the bottom.

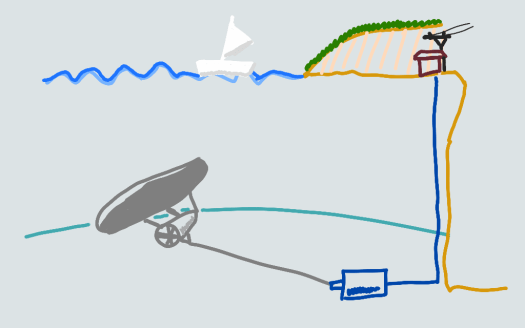

Another way to think of change, however, is like a stack.

In this model, you stack different choices on top of each other, perhaps continuing to use them all at different times.

You may try out two approaches at the same time, like two boxes stacked side by side, before moving on to try something else.

Continuing with the energy example, you may have gas-fired heating, but also install a wood-burner – going back to using firewood for heating.

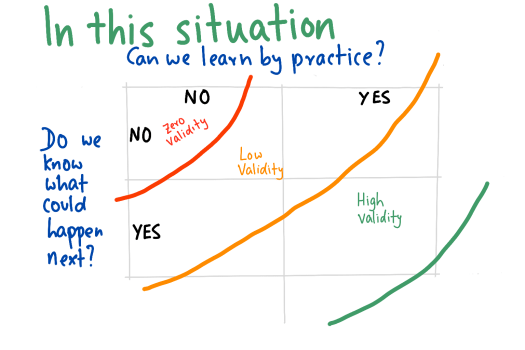

Neither model is quantitative – but they provide different ways of looking at a situation.

Take software, for example. Let’s say you have a system that is a significant innovation on what is already there.

If you think of change like a ladder, then you need to persuade your market that they have to switch from what they are doing to your product in order to benefit.

If you think of change like a stack, then what you need to do is persuade your market that what you have builds on what they already have to create more benefits than they enjoy right now.

There is some evidence that the stacking model is a more accurate depiction of how people actually make choices than the ladder model.

The main difference is that the ladder assumes that people need to make a choice between one thing and another. This OR That.

The stack assumes that people want to hold on to what they already have and choose things that build on existing investments. This AND That.

Focusing on what people want will probably be more effective than telling them what they need.