One of the oldest and best known proverbs is a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

This way of thinking is so ingrained in us that we accept it unquestioningly.

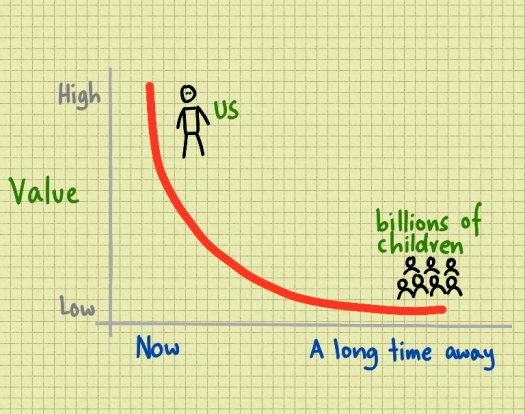

We give more importance to what is happening now than what may happen in the future when making decisions.

The simple instance of this is that many people will take a small reward now, say £10, in preference to a larger reward in a year’s time – say £20.

Given a choice between waiting a year for £10 and two years for £20, they will often choose to wait the two years – what’s the difference between a year or two?

It’s a struggle to pass up chocolate now to avoid the weight gain that may accumulate in a year’s time.

This way of thinking is endemic in business.

Managers spend a lot of time focused on the short term – cutting costs and deferring spending now to protect short term results.

In the long term the costs are almost always higher as we take action then only when compelled to by a failure or catastrophe – at which point we are forced to pay whatever it costs.

The economics of this approach is summed up in a term called discounting.

We discount the future – on a linear basis for accounting, on an exponential basis for investing and on a hyperbolic basis (possibly) for impulse purchases.

Let’s spend that money on a new telly now because putting that money in a retirement pot is so much less appealing.

Our future self, sat in a retirement home, will appreciate that telly so much more when sat waiting for the weekly visits from our family.

But that’s simply over-dramatic. We could die tomorrow – we should enjoy things while we are still around.

But we probably won’t die tomorrow.

In many parts of the world the chances are that we will live longer than previous generations and, for the first time, we may be poorer than our parents when we grow old.

Future generations will think up new ways and come up with the technological solutions they need, so we should put ourselves first and the earth could be destroyed by a comet at any time.

Except we can be pretty confident that a future will arrive – and if it’s accompanied by climate change on a vast scale – the amount of investment and technology required to deal with it may be beyond the capabilities of those future generations.

Think about it this way – a discount rate of 5% over 500 years results in a number that looks like this: 39,323,261,827.21.

That’s 39 billion, give or take a few 100 million.

A pound we spend now on ourselves, at that rate, would be worth £39 billion to someone 500 years from now.

That perhaps still doesn’t compute…

The point is that the decisions each of us makes now impact the lives of billions of people some time from now.

We need to try and make wise ones.