Friday, 7.58pm

Sheffield, U.K.

There are only two lasting bequests we can hope to give our children. One of these is roots, the other, wings. – Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

I have been thinking about how digital content is so easy to make and also so easy to forget about. If you keep a journal in digital form, for example, it weighs nothing, takes up no space. It’s simply a file in a space somewhere and it’s easy to forget it exists. And if you forget it then it’s as good as gone. And it will really be gone when the last hard drive has been thrown out and the webserver deletes your pages.

I read somewhere, or heard a news report, that there are moments of the history of this new century that are hard to find, that may have been lost. They were recorded on media that is old and obsolete, that has been overwritten or deleted or corrupted.

In 2015 I remember writing a sentence that said something like “If it’s not online it doesn’t exist.” It was an alternative to a thought I’d held for a long time before that which was “If it’s not written down, it doesn’t exist”. I wrote that first sentence down, took a picture of it and used it in a blog post. On a website that I can’t remember creating. In a folder I will struggle to find.

I am beginning to think I was wrong. Not about writing things down but about the online part – about the digital part – because unlimited space creates its own problems, not the least of which is why we need so much.

Here’s the thing. If you own a digital camera or a phone you’ve probably taken thousands of pictures over the last ten years. Many of us are too busy to do anything with that material – one day we’ll sort it out we think. But sorting takes time – organising stuff takes time. So we put it off. But if we put it off for long enough it’s like having no record at all – there is a gap in your history, one that used to be filled with photo albums and diaries, but now it’s gone. The abundance of the digital age threatens an unexpectedly dark age, one where there is no material to look at.

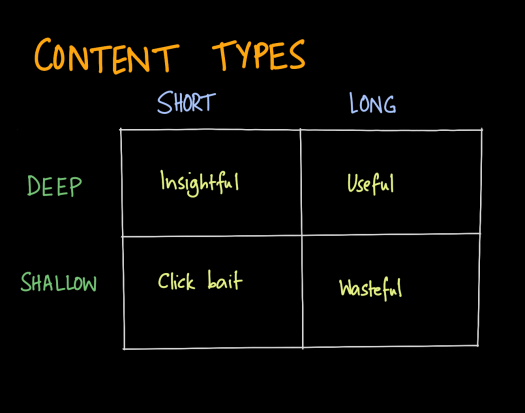

Social media companies exist to harvest your attention. They are starting to realise that your feed, the scrolling list of things that you look at, is insufficient to keep your attention. I heard a segment on the news recently that said their plan is to make their platforms more engaging, more interactive, more ephemeral, more like the real world. This is a “metaverse” a world with which you have to interact like you do with the real world. Where you have to pay attention when something is front of you or it will vanish, never to be seen again. Like a sunset. If you don’t see a sunset when it happens you won’t see the same one again.

What we end up with, then, is a world where we interact with everything but we don’t pay attention. It doesn’t matter whether the world is real or virtual, it’s experienced but not… seen.

To understand the difference you have to think like a photographer. I grew up with a film camera, one with 36 shots, and you had to pay attention to what was in front of you to try and get a good picture. These days you take 200, review them instantly and think you’ve got it. But that’s just looking, not seeing.

I think I’m falling out of love with digital – perhaps because I’m a digital immigrant rather than a digital native. Paper exists in a way a text file does not. There are innumerable advantages to having digital tools – but they should complement rather than replace one’s photos and notebooks.

And my plan is to tilt the scales, get the balance back towards the analog and see what’s really happening around me.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh