Saturday, 7.45pm

Sheffield, U.K.

There is always another way to say the same thing that doesn’t look at all like the way you said it before. I don’t know what the reason for this is. I think it is somehow a representation of the simplicity of nature. – Richard P. Feynman

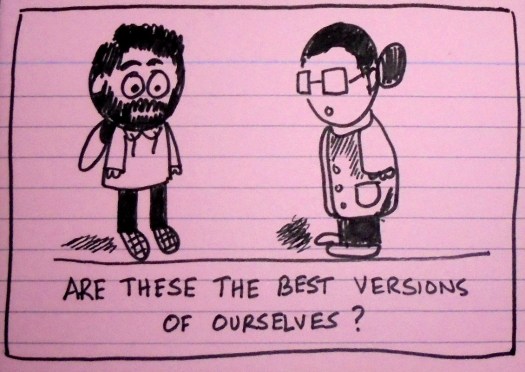

In my last post I looked at how children approach art and how their relationship with with it changes over time, starting with unselfconscious “making” and then stopping when they start to realize that what they’re making is “not good”. And that’s a feeling that doesn’t ever leave us and, for many of us, we grow into adulthood not being good at the arts – not being able to draw or sing or dance and perhaps never going back to it again.

One reason we don’t go back, perhaps the biggest reason, is that it takes time to get good at something and, as we get older, we have less and less time. By the time we reach the ripe old age of eight the chances are that we know what we’re good at and what we’re not good at and know where we should spend our time. This probably has something to do with the 10,000 hour rule – if you start playing the violin at age 2 and practice three times a week until you’re 8 for 2 hours at a time, you’d have gotten in just under 1,900 hours. If you grew up in a household of musicians you’d have been exposed to music all that time. So, when it’s time to pick extracurriculars you’d probably go for music and when it’s time to get picked to play – that’s probably going to be you and the rest of us are going to stand in the background and hope no one see us.

Now, while there’s the whole thing about the 10,000 hours being about world class performance – it just so happens to be the amount of time you’ll spend on stuff you like doing all the way through school and the time you’ll spend on the career skills you learn in those first few jobs and you’ll end up being pretty good at that thing you do. But at the rest, not so much. So you stop.

But, of course, the point is that you don’t have to be world class at everything. You don’t even need to be good. You just have to be able to do stuff that makes you feel good and being able to do things like draw and sing and dance make you feel good but they are so scary to learn when you’re an adult and want to be good and, more importantly, hate to be seen as being bad. According to Josh Kaufman you need around 20 hours to be able to do something to a reasonable standard. And if you follow Tim Ferriss you can be world class if you play the rules rather than playing the game.

But I think the first thing to get clear on is whether you want to make money doing this other thing or not. If you already make money in one way – from a job or a profession or whatever – then you should keep doing that. The definition of work, as I understand it, is doing something that you would rather not do. So, make that thing bring in as much money as possible, preferably taking up as little of your time as possible and spend the rest of your time thinking about your art. And get clear that you’re not doing it for money – that helps. Eventually, if you’re lucky, your art may bring in the money but you need to be clear that it’s not about that. The rule to remember is this – if you do something and you get paid right away then you’re doing it for the money. If you do something and then some money maybe turns up, much much later, then you’re not doing it for the money.

Now, once we’ve got that straight, and this is me talking to me as much as it is to you, we need to look at the thing we want to do – and for me that thing is figuring out this whole drawing and writing thing because there’s something in there that intrigues and interests and excites me. The title and subtitle of this blog weren’t there from the start, they’ve emerged over time as the elements that persist in my work, using handmade artifacts – yes, words and pictures are handmade – to make sense of first the business of business and now the business of living.

And I’ve got to feel my way into a position of balance. And I won’t get there by thinking but by doing and making and the more of that I do the more what’s important will become obvious. Why do I think that? Well, it always has. When you pay attention to something then you start to see more and that seeing seems to make stuff visible. Stuff that was there all along but that you didn’t have eyes to see yet.

There’s something here that has to do with the story you tell yourself. Stories seem very important. After all, your basic biology lets you figure out the really important stuff – whether to stay where you are or run away. But the human part of you, then, is all about the story. The changes are that right now if you had nothing else you had to do you’d sit back and immerse yourself in a story, a book, a film, something that took you over. A business plan is a story. Your own goals, life plans, motivating messages are all stories you tell yourself. Science is a story that you can check out for yourself.

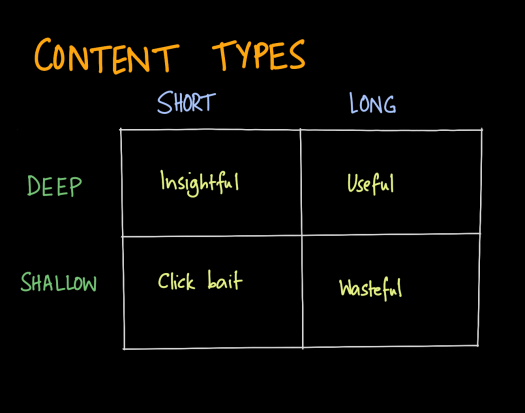

What’s the best way for you to tell the story that matters to you? I started yesterday with a child’s drawing. At the other end is a photo – a picture of reality that is as detailed as you could probably want. You could tell your story just using words or you could use a movie, a hyper-realistic graphic novel – any kind of media that you’re qualified to use. Unfortunately for me I’m not qualified for any of those other than perhaps typing out words. But maybe cartoons will help, cartoons that help me work through ideas rather than just relying on words. Perhaps one like the image that starts this blog – maybe that’s a form of representation that can work with the limited skills I have to get me where I want to be.

So… as I carry on do I look at the technicalities of cartooning and writing or do I try and explore a space by asking questions and seeing if cartoons can help me. There are lots of people who are much more qualified for the former activity – so perhaps I stick to the latter. Or I can try one approach and change later… there are no restrictions, after all. Maybe we just have a chat and see where it takes us.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh