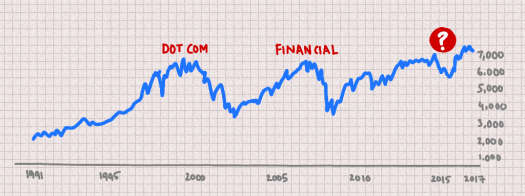

If you entered the world of work after 2008, your experience is probably one of sustained growth where things have only gotten better.

Since the financial crisis, which resulted in markets falling to a low in 2009, the world has seemed to be on a path to recovery. Stock markets have risen, houses prices have remained stable and many people are employed.

The FTSE, shown in the chart above, has risen from under 4,000 in 2009 to over 7,000 today, an increase of 75%.

But, as Santayana said, those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

We live in a world where valuation and value are not the same thing.

The dot com crisis at the start of the millenium resulted from ascribing absurd valuations to companies that were little more than dreams and wishes.

The financial crisis in 2008 happened when complex contracts designed to spread risk turned toxic and concentrated it instead, corroding trust – the grease of modern economies – and bringing the whole financial system to a grinding halt.

And now we come to 2017.

Is the steady rise we have seen over the last seven years because of a real recovery or because of something else?

The internet has grown up after all – it’s now transforming how we live our lives and do things. So perhaps the new digital connected economy is helping economies change and grow?

An alternative explanation is that governments have pumped vast sums of money into the system to keep things working.

This money is injected through financial institutions and has to go somewhere – it has to be “invested”. So the money goes and accumulates in certain places – companies, commodities, bonds that promise returns.

The issue is that there is more money chasing these assets that have returns, and so people are willing to pay more for them, and as a result their valuation increases.

Since BREXIT, the UK index has risen because a weaker pound makes the largest businesses in the UK more competitive globally, increasing expectations that their profits will rise and pushing up their valuations.

Conversely, when the exchange rate drops, the valuation of these businesses falls as well – the FTSE 100 is inversely correlated with interest rates.

So, what should you do now? Should you sell everything and walk away from markets? Should you double down and buy some more?

As Blaise Pascal said (almost), all of humanity’s problems stem a person’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.

The markets will go up and down. Given where they are, it makes sense to be prepared both psychologically and financially in case they fall once again.

The thing to remember is that percentage changes are not symmetric. A 75% rise only needs a 43% fall to wipe out all your gains.

At this point, it might make sense to invest with a mindset that is prepared to have your investment take over 10 years before it shows a profit.