Tuesday, 8.04pm

Sheffield, U.K.

I tend to approach things from a physics framework. And physics teaches you to reason from first principles rather than by analogy. – Elon Musk

How do you make something useful – something relevant – something that’s so interesting it grips your reader or customer and draws them in irresistibly?

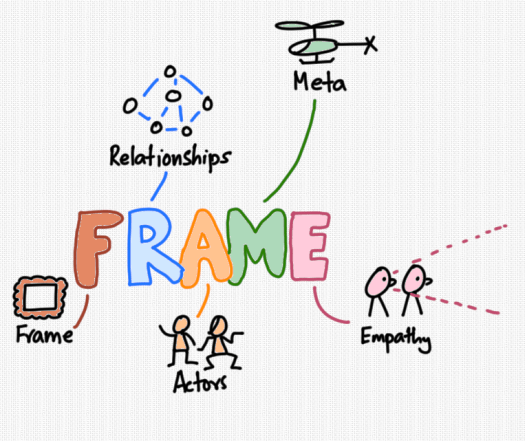

You do that by understanding them inside out – by learning and discovering exactly what they want and need and then giving them that. But how do you go about doing that? The FRAME model may help.

There are five elements, one for each letter of the word. You can start anywhere, but you need to have all of these in place to make progress.

Start by thinking about your Frame. Work out what’s in and out, what matters and what doesn’t. The tighter the frame around what you’re interested in the more focused you’re going to be – and the easier it will be to figure out what you need to do. Sometimes you can make the frame too small, and you don’t see enough of the picture. Getting the balance right is key. Think of it like taking a picture of your family – you need enough background to know where you are and what the context is but you need to be tight enough to see them in enough detail. There’s an art to framing – and that’s why it’s important.

The next two elements go together and that’s Actors and Relationships. Actors can be human or not – you might have a person in a role, a robot carrying out a function or an algorithm processing a data set. Actors do something – they play a part in the frame you’ve created. The way they interact with other Actors is shown by drawing the Relationships between them. These connections are what make things happen.

The next element is Meta – the helicopter view. Take a ride up and look down at the frame you’ve drawn, the actors you’ve placed in that frame and the relationships between them. Have you included everything you need to include? Is the level of detail right? Can you see the main features – the natural ones and the artificial ones? The Meta element is about seeing the big picture – knowing why the terrain below is set out the way it is.

The last element is Empathy. See your creation through the eyes of your user or customer – one of the human actors that’s living in your frame. You’re building this thing for them, so what do they experience, what do they go through and does it work for them? Does it deliver for them? Does it delight them? Does it delight you as you see the world you’ve created through their eyes?

Does this model work in practice? Apply it to a company you know – something like Amazon? Amazon does retail – it helps “consumers find, discover and buy anything”. It’s build a formidable logistics network, with a group of human and non-human actors bonded together with relationships in a remarkable display of engineering. If you take a helicopter view they’ve spread out across the landscape doing things ranging from technology to warehousing. And in the middle of all that they aim to be the “Earth’s most customer centric company” – they empathise with their customer’s need to get what they want, fast. And they deliver on that.

Is this model complete? No – it can’t be. Real life is too complex and we can’t capture everything. Is it useful? Try it for yourself and see.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh