Saturday, 8.31pm

Sheffield, U.K.

Long-term commitment to new learning and new philosophy is required of any management that seeks transformation. The timid and the fainthearted, and people that expect quick results, are doomed to disappointment. – W. Edwards Deming

This is a fascinating time to watch what is happening with businesses as they respond to the impact of the Covid 19 virus.

We’re in a position where we can see what people think, how they’re affected, what they’re feeling and doing because they tell us on social media.

Now, we have to remember that there is real suffering, real tragedy – and people trying very hard to keep the world’s population safe so that more people don’t die.

And while it’s tempting to try and point fingers, to blame individuals and their behaviour for the reason we are where we are, what we need to always remember is that’s the most basic error we usually make.

We blame people for how things work out rather than the system – their situation.

We are where we are because of the system – the systems involved.

The systems of global transportation, of holidays, of long supply chains, of office work, of entertainment – the myriad other systems of modern life.

All these systems create the conditions that enable the spread of this virus – and it’s not surprising that the way governments have chosen to contain it is by stopping those systems from functioning at all.

Which leads to the obvious question.

What stops this from happening again when those systems are restarted?

Now, we’re not going to solve all those global systemic questions in one go, but an interesting and topical one to look at is the way in which we work.

For the vast majority of people who do non-critical jobs there is now a way you used to work.

You might have commuted to an office and spent the day in front of a computer.

You might have had meetings with a manager, with co-workers, with suppliers and clients.

You might have socialised, gone out for drinks, gone to networking events.

What’s happening now, it seems from the number of pictures that are being put up of brand new home working spaces, is that the office has come home.

People are jumping onto team calls, having chats with managers, setting up social mixers online.

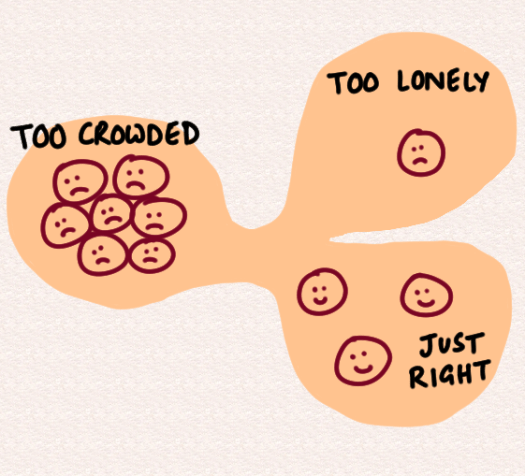

Nothing has changed except for the physical distance between people.

As someone online said, it’s social distancing, but not distancing yourself from society.

In effect, there’s a thin layer of remote working technology that enables you to carry on working exactly as you’re doing now.

So that’s good for people who like how it is now.

It’s good for managers who like having the ability to check up on people – perhaps to the extent of having a tool that takes screenshots of their screen every so often to make sure they’re still working.

It’s quick and easy and people are finding that this whole remote working thing is quite easy after all.

They just thought it was hard – and it turns out there is no difference at all.

And that shouldn’t surprise you.

It’s easy because the large tech firms have spent the last several years trying to create tools that let you do the same thing you’re doing in the office using their technology.

If you weren’t doing it that didn’t mean the tech didn’t exist – it just meant you weren’t aware that it did.

And now you are – subscriptions for these tools are skyrocketing and demand has increased.

They built something that would work for you now – and unsurprisingly, it does.

The tragedy is that it does.

Because we’re going to miss out on the real potential that this crisis offers us – a way to change the way we’re doing things entirely.

In reality, we could be arranging work so that it works to fit the unique circumstances of each individual.

We could create working practices that enable more diversity – that use the same kind of remote working technology but that make it easier for disabled people to participate in work, for disadvantaged groups to access opportunities.

And, for your own workforce, you could create working practices that work for them – rather than for the most vocal or for the dominant managers.

But that’s not going to happen unless you change the system – and that’s the responsibility of management.

Will management respond in a way that looks to improve the system?

Or will they look for the quickest way to carry on doing things the way they’re working now.

The answer shouldn’t surprise you – because the other option requires the willingness to learn and study and try and few people have the time to do that.

So, in the short term, the forced stoppages of systems will clear the air, remove pollution, heal the planet.

And then it will go back to normal.

Won’t it?

The fact is that without changing the system the underlying mechanism will remain the same and produce results that are the same as before.

If we want to create better, more fulfilling lives for people – we have to work on improving the systems they live in.

If we want a cleaner planet, one where we pollute and emit less and where we consume fewer resources, we have to work on the systems.

This virus is not going to change our world.

It may interrupt how we live for a while.

But if it’s short-lived, we will probably go back to normal quickly.

If it lasts for a longer time then we may start rethinking how we do things.

But the change will still have to come from us.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh