In the military, as in any organization, giving the order might be the easiest part. Execution is the real game. – Russel Honore

Every once in a while you look around and wonder what people do at work.

One answer is found in Robert X. Cringley’s 1993 book Accidental empires.

In his book he talks about the way companies grow – and likens what happens to a military operation.

As an army brat I grew up conscious of uniforms and rank; packing light and always being ready; and learning that I didn’t like being told what to do by anyone else.

There’s a place in an organisation, however, for almost any kind of individual – whether you fit in or not depends on what stage of growth the company is in.

In a startup, for example, you’re low on resources.

You don’t walk into a startup and get an induction and a tour and a few days briefing.

When you’re employee number one or number two into a startup you probably spend the first day building your computer.

I did anyway – I think I worked off my own machine for a while, actually.

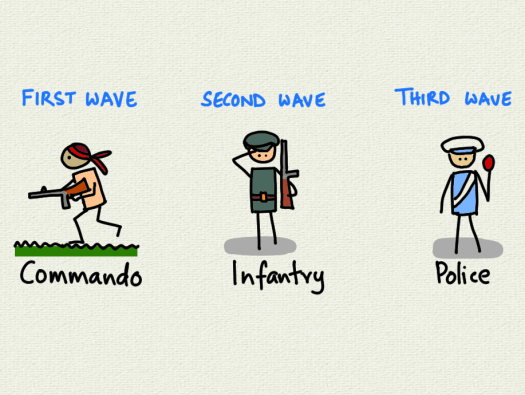

The point is that the people you want on your team in the early days are the ones that think and act like commandos.

If you want to invade a country you don’t stroll up with your army.

You send in commandos first – so they can blow up roads and supply lines and generally soften the target before you commit your main forces.

The job of a startup is to take the beach – establish a presence in a market.

That means nothing matters except customers and product.

All the rest of the stuff can wait – policies, HR, timesheets, legals. None of those matter until you have a product or service and customers ready to try you out.

When you’ve established your presence, that’s when you send in the infantry.

These folk get into their trucks and tanks and roll up.

Yes, they’ve got to do some work. They’re the main force and they take over the job of securing and expanding your presence, fighting their way through the rest of the country.

That’s the scale up stage of your startup – when you go part the three or four people who were there from the start and bring in people to do jobs – jobs that didn’t exist till you created them.

Now, once you’ve taken control of your territory you need to get settled for the long haul.

This is when you need the administrators and the police – the rules and regulations that make for a society.

That’s the point in the life of the company where you bring in people who write policies and administer them. The ones who make rules and make sure you all follow.

This is when it becomes important to monitor and measure and watch over what your people are doing.

Customers are a lot less important now – what’s important is control and process and standards.

The first stage is exciting and you get a chance to be creative – but there’s also a very real chance you’ll fail – but also a chance you’ll do very well.

The last stage is safe and you’ll have a good career – perhaps end up being a well-regarded professional.

The middle is a solid place to be – good experience that you can take to any other company looking to scale up and build its business.

The important thing really is figuring out which one of these three types of workers you are – and then checking if you’re in the right kind of company.

If you’re a commando, you won’t last long in a third-wave company – they just wont know what to do with you and your habit of not following the rules.

And, a police officer in a first wave company will have nothing to do – everything will need policing because it’s all being done too fast and doesn’t follow the rules – but no one will stop long enough to listen.

But what’s important is knowing what’s right for you.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh