Tuesday, 7.57am

Sheffield, U.K.

Sustainability can’t be like some sort of a moral sacrifice or political dilemma or a philanthropical cause. It has to be a design challenge. – Bjarke Ingels

I’ve been thinking of how to market environmental consulting products for a long time.

I remember sitting in a marketing training program so 20 years ago, and coming up with four words that mattered to clients when trying to make choices.

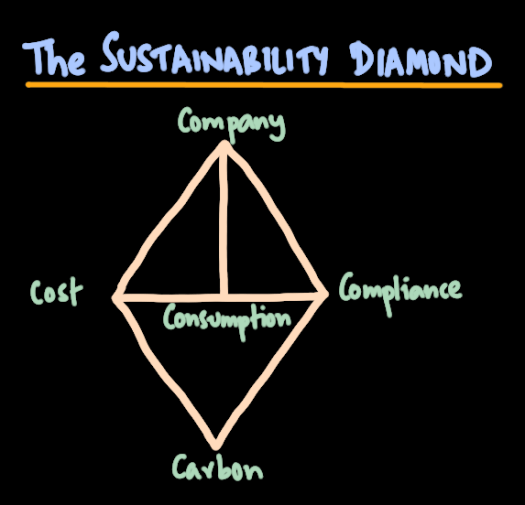

Cost, consumption, carbon and compliance.

These four words were, at the time, seen as quite technical – and I had to play with them to make the messaging easier for a lay audience to understand.

But the words themselves have stayed relevant.

Over the decades, companies have focused on one or the other at different times.

A good way to think about this is what I’m calling the sustainability diamond.

At the top of the diamond sits the company. Or any other organisation structure that has to think about its use of resources.

Resources have a cost – using gas and electricity results in bills, raw materials have to be purchased.

Companies actively track current and expected future costs – helped by traded commodity futures markets.

That’s where I started my career – building systems to look into the future and make decisions based on where prices were now, and where they were expected to go in future.

A bad trading decision could result in a swing in prices of 50% either way.

Then there was consumption – how much of the resources you used.

The easiest way to save money is not to burn fuel, to use fewer resources.

But it’s also a hard source of savings. It takes time and effort to identify where you can make improvements.

Energy and resource usage can easily become wasteful if you don’t monitor and control what’s going on.

In the middle of my career consumption management became more important.

As we added more renewables to the grid, the idea that we could manage demand – pay consumers to reduce their usage if supplies dropped – came to the fore.

This meant that if the wind stopped blowing and energy supply fell, we could balance the system by dropping demand rather than having firing up a gas turbine to fill the gap.

But to do this you needed a good handle on usage – and we built systems to monitor this on a minute by minute basis.

Cost considerations came screaming back after a series of events – the Fukushima nuclear reactor, the rise of shale gas.

But for the last ten years or so, the focus has been on compliance as new rules came in – most importantly net zero targets in many countries, starting with the UK.

Companies had to start complying with these new rules – measuring and reporting on the resources they used and starting to make plans to make their companies more sustainable.

These then are the three facets of the diamond – managing cost, consumption and compliance are the drivers for taking action.

And the action we take has a result in terms of carbon.

Recently, it’s become clearer and clearer that we should think of carbon like we think of dollars – a way to normalise different measurement systems.

For example, we convert all currencies into a standard one, like dollars, if we want to get a like for like understanding of how a firm is doing financially.

Measuring outcomes in terms of carbon allows us to do the same – taking therms of gas, kilowatt-hours of electricity, litres of diesel, purchasing spends – and putting them all into one, relatively consistent, unit. There are issues with conversions and emission factors, but on the whole we end up with something that is consistent and comparable over time.

The Sustainability Diamond may be a good way to keep the big picture in mind while focusing on any one part at a particular point in time.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh