Wednesday, 9.00pm

Sheffield, U.K.

Society is always taken by surprise at any new example of common sense. – Ralph Waldo Emerson

There is a lot of stuff happening in the world right now – people are scared and fearful and worried about what’s going to happen to them, their families, their livelihoods.

And they’re talking about this – about the impact it’s having on them – millions of voices having their say.

And it feels like other people are listening.

When you think about the hard choices that governments are making – you get a sense that the response, in fairness, is on the right track – that there is method behind what is going on.

What people do for work seems to be recognised in terms how it can be done – rather than how a manager wants to do it.

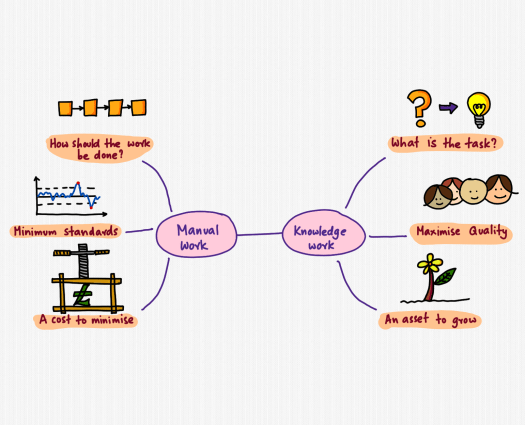

Some services are ones that need people to be in certain places at certain times – healthcare, retail logistics, bin collections – and so we need to organise society to make sure they can get to work if they can.

Other work can be done from anywhere – and it makes no difference to these people whether they work at home or not.

In fact, all things considered, they might prefer to work from home but suffer through a commute because their boss comes from a generation that believes that work happens in the office.

And then you have work that’s affected by the policies that have been put in place to contain the spread of the virus – the entertainment industry, travel, hospitality, child care, construction – where work simply cannot be done.

Now, what’s going to happen is this.

People who need to be somewhere will be helped to get there.

People who can work from home will start doing so.

People who are in difficulty because of what is happening will be helped.

And, in several months, things will be back to normal.

And during that time, the damage will be covered by the state.

Hopefully.

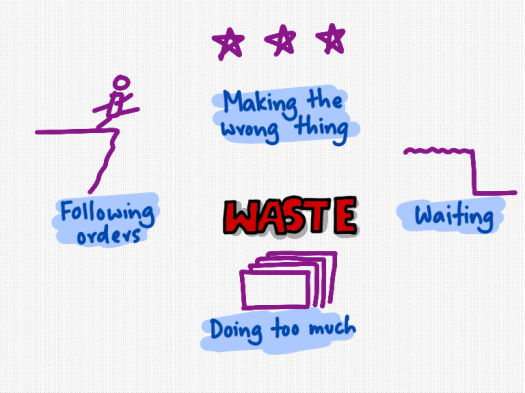

Now, when we go back to normal – will we return to a world where a virus can stop everything functioning around the world in a matter of months?

Or will the new ways of working we put in place – ways of working that, one assumes, are more resilient in the event of this kind of threat – stay in place?

Will we see a wholesale shift from office based work to home based work?

Will that result in demand for different kinds of spaces?

Will the main reason we go out become because we want to socialise – and will the entertainment industry get a boost from that, while office space takes a hit?

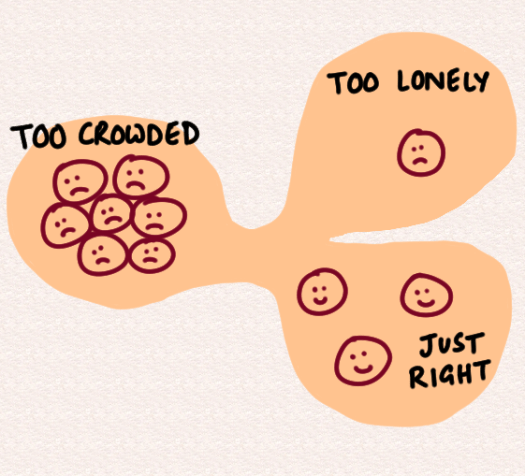

There are lots of people who believe that working from home is the wrong thing to do – that people need the social and control structure of the office.

This assumption is about to be severely tested over the coming months.

The SAAS world will see a surge in interest in off-premise solutions.

Commutes, for those who have to, will become easier as the roads empty of non-essential traffic.

Carbon should go down.

This is a difficult situation for many – there is no doubt about that.

Some people will see this as judgement day, as doomsday, as something that is punishment for the way we live.

Others will be more optimistic – believing that society is better placed to weather this storm than we have ever been in the past.

I am in the optimistic camp.

And I would hope that once we go through this hard reset on our nineteenth century attitude to work – we make the choice not to go back.

Because the new way is better for us as individuals, as a society and for the planet.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh