Thursday, 10.32pm

Sheffield, U.K.

If you are too afraid to offend anyone, then I’m afraid you may not be able to do anything remarkable – Bernard Kelvin Clive

Yesterday I picked up The essential Drucker – a distillation of the writings of arguably one of the greatest management theorists of his time.

I particularly liked his idea of management being something that applied to “every human effort” and how its real value lay in its ability to unite technology and society in the service of humanity – arguing that it is a liberal art in the humanities tradition.

All that I liked.

And then it rather went downhill from there, as the text started talking about objectives and missions: things that I am not convinced actually work that well in real life.

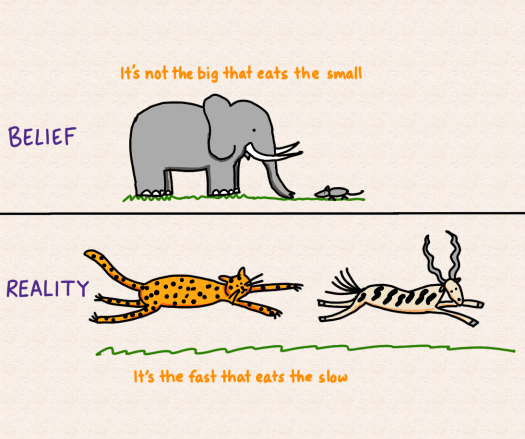

The reason for this is that what happens has much less to do with what you want to happen and much more to do with the context in which you operate – the structure is usually responsible for the majority of the results.

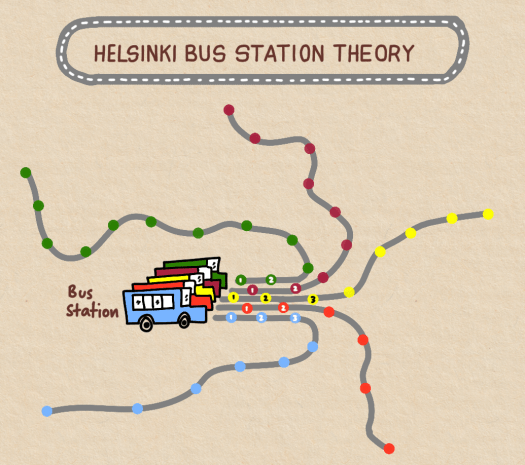

Now, this is not easy to always talk through – and a model can help think through those structural issues.

So, I thought I’d pick up Seth Godin’s Purple cow and have a first pass at a model and see if it actually helps.

Godin’s book is about being Remarkable – like a Purple Cow would be if you came across it.

But you can’t just decide that you are going to be Remarkable – set that as an objective.

Well, you could – you could dress provocatively and behave outrageously – but I don’t think that’s the point we’re trying to make here.

The point is being the kind of entity that is remarkable – the “remarkable” bit is an emergent property of the business you create – something that is about the business but that you won’t find in accounting or marketing or sales but in the customer experience as a whole.

Okay, enough technical talk about systems thinking – here’s how to apply this first pass model.

Say you want your business to be remarkable – ask yourself – do you stand out in any way?

Being like everyone else might seem like a safe way to be – but that way your business will never grow beyond a certain point.

And again, it’s not enough to just say you’re different – you actually have to be different.

But how do you do that?

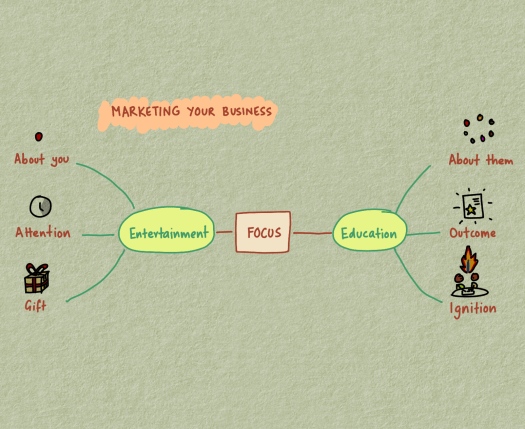

One good way is to identify a niche that you can target and dominate.

For example, if you’re a hair dresser in a salon, you could just cut hair – or you could specialise in a particular hard to do technique that is remarkable.

But how do you find that niche?

You find people who care about something you can do – who care to the point where it’s more than a hobby and less than an obsession.

A kind of feeling captured, Godin says, by the Japanese word otaku.

You learn from these people about what they need – give them that – and because they are early adopters who will talk about you a lot – you’ll find that word of mouth marketing helps you build your business.

But why should they listen to you?

Because you listen to them and give them something that tests the limits – gives them more – better, faster, cheaper, higher quality: something that they will love.

Now, when you get all this right you’ll find that your business takes off – it just explodes.

But nothing goes on forever – eventually that momentum will stop, the market of early adopters will dry up and you may move into a more mainstream world, where not standing out and being safe start being important, and you slow down and earn what you can for the rest of your product’s lifetime.

But that can be left to your managers – you should be working on building your next remarkable venture.

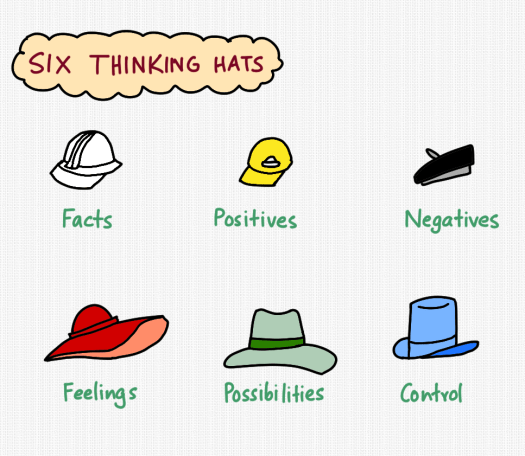

Now, I’m not saying this model is correct or complete.

Always remember that all models are wrong, but some are useful.

The question is whether this model is useful in thinking about whether your business, as it stands right now, is remarkable.

And if it isn’t, does it highlight areas that you could work on?

The thing to note is that this is not a process – not something you can follow.

Every part matters and you need it all to work for that “remarkable” property to emerge eventually.

My feeling is that this kind of model is more useful in helping us ask questions about our businesses than the relatively mechanical task of setting an objective to be remarkable.

If you focus on what’s inside the envelope – the elements of structure – and work to improve them, then what people see will be remarkable.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh