Friday, 7.46pm

Sheffield, U.K.

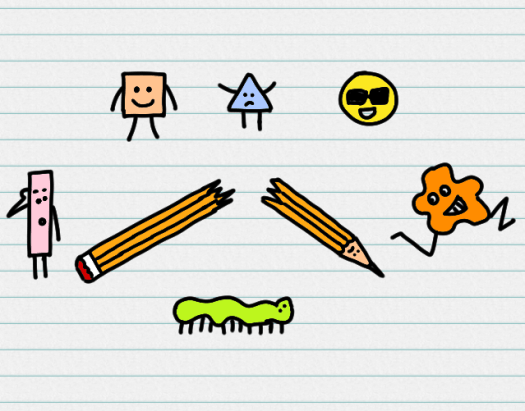

We are the only species on Earth that observe “Shark Week”. Sharks don’t even observe “Shark Week”, but we do. For the same reason I can pick this pencil, tell you its name is Steve and go like this (breaks pencil) and part of you dies just a little bit on the inside, because people can connect with anything. We can sympathize with a pencil, we can forgive a shark, and we can give Ben Affleck an academy award for Screenwriting. – Jeff Winger in Community

A few things haven’t gone the way I would have liked today.

I don’t usually worry much about things not going right – but when they don’t it’s still stings a little.

It will pass – it always does.

But, it gets me thinking about a few things – but I don’t know if the pieces will come together in any coherent way.

But let us have a go.

We start with a book called Bureaucracy: What government organisations do and why they do it by James Q. Wilson.

Wilson makes an unpromising start by quoting James G. March and Herbert A. Simon as writing that “not a great deal has been said about organizations, but it has been said over and over in a variety of languages.”

Theory, this implies, is a waste of time but it is unlikely to be of any practical use.

Well – that’s it for this blog then.

Luckily, there is more, and it is useful.

First, there is a distillation of concepts one can use to understand bureaucracies – and organisations in general.

Ask yourself what tasks the organisation does – not goals, but the critical tasks it must carry out.

Then ask what gives the organisation its sense of mission – is it pride in what people do, a religious calling, a sense of honour and duty?

And then ask how autonomous the organisation is – how well it can make decisions.

Then, if we skip to the end Wilson quotes James Colvard on how to run organisations better – have “a bias towards action, small staffs, and a high level of delegation based on trust.”

And here we get to a central point – management is not about tools and it is not about systems.

It is about delivering something – a mission – what a customer needs – something that makes things better.

From this, we can jump to Federalist Paper No. 51 which has some hope for people wondering what is happening in the world right now – especially when it comes to people and governments.

James Madison argues, in his paper that:

“The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

In other words you need institutions – independent centres of power that balance and check each other to maintain freedom and democracy in a society.

And you need the same in an organisation – excessive centralisation leads to ossification, excessive decentralisation leads to dissipation – and you need a balance of loose and tight to keep the system together.

So, what about the broken pencil?

The point, I suppose, is that organisations act in ways that don’t always make sense.

What wins in one situation loses in another – and we often make the mistake of thinking that it’s the systems and processes that are the organisation rather than the people.

But the people are also the system.

As humans we can connect to anything – we can take a bunch of shapes, add facial features and emotions and give them personalities and feel like we relate to them in some way.

And as humans we are impossibly complex.

Something that seems right to one person is completely wrong to another.

When I fail, it is often less because what I did was a failure but because what I did was wrong in the eyes of others.

Or maybe it was just wrong – it’s hard to tell.

But the thing is to keep going – because what else is there to do?

We have the ability, it seems, to project human nature onto everything around us.

When we understand our own – then perhaps we will find the right place for us.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh