Thursday, 9.26pm

Sheffield, U.K.

The first forty years of life give us the text; the next thirty supply the commentary on it. – Arthur Schopenhauer

CNN had a story this week that reported that we age significantly at two points in our lives, ages 44 and 60.

That is very precise. And perhaps correct, from my own experience of the first significant point.

Robert Kiyosaki had this story of life being like a football game – you started the game, you got a quarter of the way through. Then there was half time. Then there was the final quarter. And then you were out of time.

Do you remember what’s happened in the game so far?

I have a terrible memory. I know people who remember everything but for me the past is a blur.

Except when I read my journal entries.

I have kept journals, on and off, in different mediums, for several years.

Perhaps going on two decades now.

They are intermittent, interrupted by life’s events but they capture moments in time. In particular, the mundane everyday, where we went, what we had for lunch, what the commute was like, what I was listening to at the time.

I don’t know what percentage of people keep journals. Perhaps the modern form is the social media feed – that’s where people go to find out what was happening back then.

But I wonder about the persistence of media, whether we will still have all this when we need to remember something.

Many of us have tens of thousands of pictures. But do we have the stories? We have videos, we can relive moments. But is that the same as remembering?

Does text still have a place in this world?

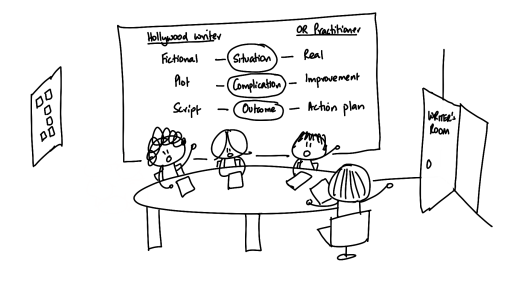

I think it does. Text, the written word, is an incredibly compact way to hold a story. We can relive stories through video, we can see the world as it was in a picture – but we can recreate the world through text.

And this is perhaps important, because a moment frozen in time is different from a moment that made you the person you are.

Thinking back to a time and reflecting on the words you wrote, a message from a younger self, a different person, someone you barely remember, feels like growth, feels like something that helps you learn and develop rather than simply see again.

Too much of anything is a problem. When you take too many pictures, have too much video, you have to live your life again to process that material. It’s time consuming and exhausting and, when the clock runs down, will probably just disappear.

A memoir, on the other hand, a book, a package of print on paper – that has a chance to last.

If I were to advise my younger self I would have said, take a few pictures but write down as much as you can.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh