Saturday, 7.53am

Sheffield, U.K.

Let him who would enjoy a good future waste none of his present. – Roger Babson

This is a continuing post series, the fifth one, as I read John Bicheno’s “The lean toolbox for service systems”.

Today we’re going to look at waste.

Bicheno says that we should approach this indirectly, not as a checklist for finding waste.

As always, we have to go and see what is happening for ourselves, trying to go from abstract ideas of what should be happening to specific things we can do to improve the way in which we serve our clients and customers.

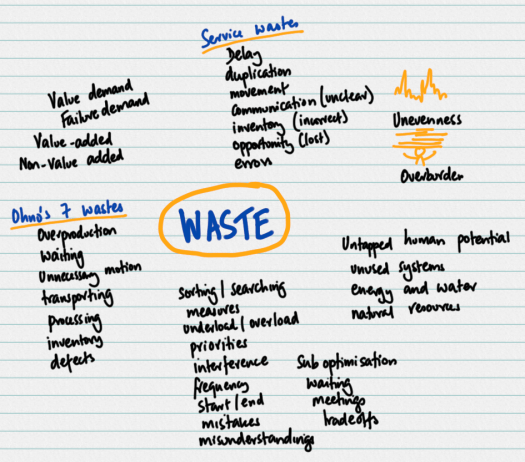

The picture above has a big list of wastes, some of which overlap – but let’s try and see what sort of things we might find.

Let’s start with the people you work with – are you benefiting from their full potential?

Working with others is challenging. We are social creatures and there are issues of hierarchy and control and relationships that have to be navigated.

How do you treat your employees or direct reports? Do you treat them like children – telling them what to do? Do you treat them like colleagues, working together? Do you trust them to do things right?

I have found that the hardest thing is to have a good working collaboration with others – it takes time. You cannot expect it to happen without effort, management tools and performance appraisals won’t make it happen, neither will silly bonding sessions or social occasions.

You need to spend time with the people you work with, talking about the work and figuring out how each person can contribute effectively.

People are often the biggest cost in a business and if they don’t bring their brains to work you’re missing out on the biggest return you can have.

Once your team is thinking together about what they’re doing and how they’re providing value you can start to dig a little deeper into the actual work that’s happening.

And the concept of value demand and failure demand come into play.

Value demand is when you work on what the customer wants.

Failure demand is having to fix the consequences of failure.

For example, if you’ve ever done a construction project you will find tradespeople will make choices to take shortcuts rather than do something in a more detailed way.

One example is whether they run cable in plastic sleeves they nail to the wall or if they chase the plaster and put the cables in the wall.

If they don’t do what you want and have to repeat the work because you don’t like the look of external wiring, that work is failure demand – you’re fixing something you’ve already done because it isn’t right.

A good percentage of service work can turn out to be failure demand – just not doing the job the customer needs.

These are two big sources of waste right there – not using your team effectively, and not taking the time to understand what the customer needs before doing the work.

I suspect, without evidence, that these two areas account for 80% of the waste in a service business.

The remaining 20% comes from stuff you can control but that people often just don’t do well.

Stuff like:

- Not having a filing system for material that makes it easy to retrieve.

- Underloading or overloading people or stages of your system

- Moving things around too much, too many touches

- Unnecessary processing

All these and more are issues to do with failing to create a flow of work, something that is even rather than uneven, and not distributing tasks well, loading different areas differently.

From a management perspective two things that don’t help are interruptions and meetings.

Interruptions kill work in progress, knowledge work in particular.

And meetings, in the standard sense, can be time sinks.

In my practice, I try and combine the two – by having regular meetings that are in the diary so I don’t need to interrupt someone in the middle of their work.

Ad-hoc calls are just not a thing anymore.

And meetings are used to go through and ideally do the work – they are working sessions where we collaborate rather than talking sessions where we talk about what needs to be done and then have to find more time to do it.

Online meetings can be hugely productive if you know what you’re doing but judging from my LinkedIn feed not many people know how to do them well.

That may be a post for another time.

Once you go to where the work is being done and start to get a sense of the waste in the system you can start to think about how you can improve it.

This starts with a mapping exercise, which is what the next chunk of the book is all about.

Having flipped through it, I don’t fully agree with some of the ideas – or, perhaps more accurately, I think they’re not enough to deal with the richness and complexity of real-world situations.

So we’ll dig into that next.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh