Saturday, 9.46pm

Sheffield, U.K.

I’m actually writing history. It isn’t what you’d call big history. I don’t write about presidents and generals… I write about the man who was ranching, the man who was mining, the man who was opening up the country. – Louis L’Amour

Did you hear Trump talk about buying Greenland from Denmark and merging with Canada and wonder what was going on?

I spent some time today away from social media.

A few months back I think I wrote about how I thought social media was a useful source of insight – how people looked for interesting things and shared them with you and the result was like having a team of researchers making sure you knew what was going on.

I’m less sure of that now.

There is probably some useful stuff but because the algorithm shows you what you’re interested in that means after a while you’re not seeing anything new.

That happened very quickly. It took around two months of writing and engaging before it was clear I was in an echo chamber.

So I stopped.

The problem is that once you cut off the information hosepipe you’ve been drinking from, how do you know what’s going on?

It’s a complicated world out there so how do you make informed decisions for yourself and your business?

I started by going back to the library.

UK cities have good library facilities for citizens and one of the benefits of paying a council tax is access to a good e-library which lets you borrow newspapers.

Like the Economist. I used to read the Economist every day. I had a subscription for a while. But then, as free sources of news came along, those habits slipped away.

But 2025 promises to be a year where shutting your eyes is not a good idea.

I borrowed a few papers and started reading. And, for the first time in a decade, started clipping articles out of the paper.

Well, using a snipping tool on the computer and saving them, that is.

It feels like an old fashioned thing to do – to clip an article.

I have a book in my library about the Mitrokhin Archives – about secret KGB operations between the 1930s and 1980s.

I picked it up in a second hand book store, mainly because within the pages the former owner had clipped and stored news stories about spies.

I clipped a story from the Economist about the economics of the Arctic, and learned that Greenland has the biggest deposits of rare earths, nickel and cobalt in the West.

Canada is also home to huge reserves of iron ore, has the largest coastline around, with access to the seas around the Arctic.

These materials are important to the West because the biggest reserves of minerals essential for batteries are in China.

And you know there are some tensions going on there.

Modern armies need technology, that technology needs these minerals.

As an aside, we also need them for green energy technologies.

So, wanting to control the places where these are found starts to make sense.

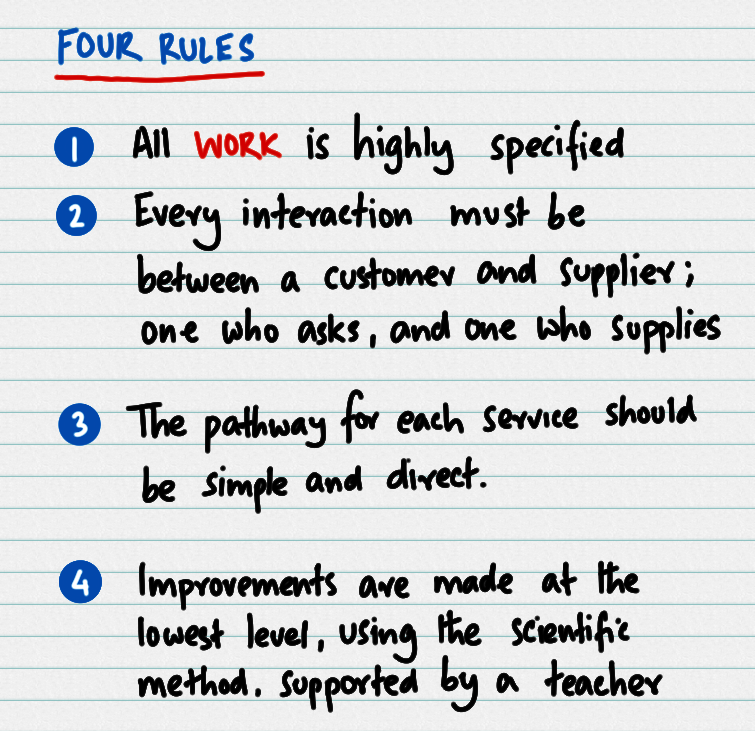

I think my resolution now, for 2025, is a simple one.

Try and be better informed.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh