If you have a complex problem to solve, do you need to build an equally complex system to solve it?

Most people, when they think of systems, visualize technology – robots, artificial intelligence, connected machines and autonomous vehicles.

A more general definition of systems includes the people that use the technology and the processes they follow when using it.

Complex systems include things like governments, religions and companies.

How does a large, complicated company come into existence?

Well – it probably didn’t start out large. It started as a small company once doing something simple. For example, General Electric, one of the largest conglomerates in the world, can be traced back to Edison and his lightbulb.

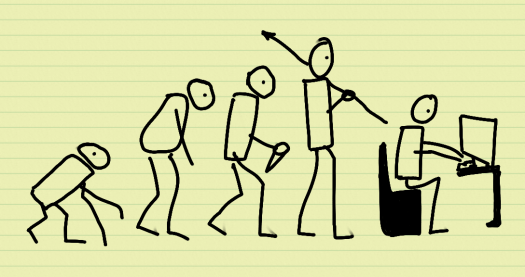

This idea forms the basis of Gall’s law, a rule of thumb from the book “Systemantics: How systems really work and how they fail” which says “A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked”.

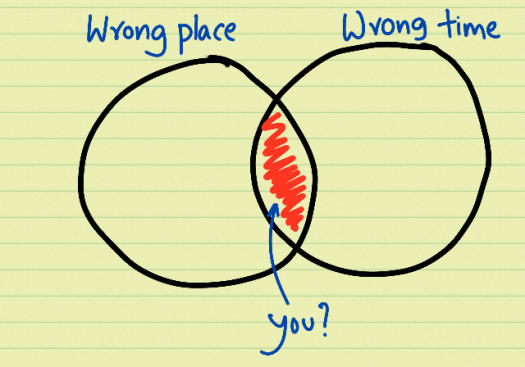

The reverse also appears to happen. A complex system built from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to work. You need to start again with a simple system.

The main problem with building a complex system straight away is that a system is simply someone’s approach to solving a problem – the system itself doesn’t solve the problem.

A complex system built without constantly testing whether it is doing something useful can end up doing hardly anything useful at all.

This is why many modern approaches to programming are “agile”, solving simple problems first and putting out software that people can try out to see whether it is actually useful.

A related observation from the book is that very efficient systems are dangerous. Loose systems, systems that hang together with some slack tend to grow larger and work better. An example of this might be the growth of the world-wide web.

The book is a slightly tongue-in-cheek commentary on systems theory, which has moved from a “hard” systems approach where people believed every situation could be mathematically modelled and solved to “softer” approaches that take into account the reality that people doing what they think is right have the inherent capability to mess up any system designed by a technocrat.

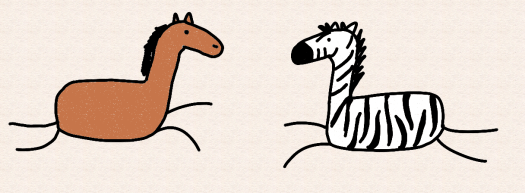

Intelligent behaviour is not something you design into a system but something that emerges from the way in which the system is arranged.

The only approach that has been shown to produce intelligent behaviour so far is evolution, and so it makes sense to prefer it when creating a new system.