Getting to Yes: Negotiating an agreement without giving in is the classic text on negotiation by Roger Fisher and William Ury, setting out an approach to something many of us do all the time.

Good agreements should be fair, wise, efficient and capable of lasting.

Many negotiators, however, start with a position – such as price and get ready to bargain.

This tends to be confrontational – imagine that this is like trench warfare, where you dig in for the long haul and try to wear the other side down.

That hasn’t really worked out well in the past.

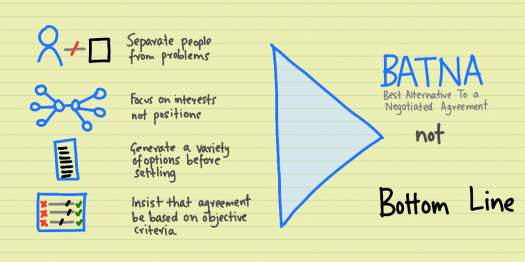

An alternative, set out by Fisher and Ury, is the idea of principled negotiation – set out as four principles to follow.

1. Separate people from problems

All too often, negotiators identify too closely with the problems they are trying to resolve and take things personally.

Winning or losing a point becomes about personal victory or failure.

We have all experienced the person that refuses to back down even when they are wrong. Sometimes we are that person.

The first step is to try and step back, untangle the personalities from the issues at hand, acknowledge and respond to the emotions swirling around us and use words carefully, listening actively and using language designed not to provocate while trying to see the other person’s point of view.

2. Focus on interests, not positions

A position is a decision. An interest, however, is the thing that led us to taking that position.

Our interests need to be put on the table, discussed and understood. A useful visual tool for this is a compare and contrast diagram, as shown in the picture above.

The idea is that the better we understand each other’s interests, the more likely we are to find a solution that satisfies both of us.

3. Generate a variety of options before settling

We often fall into the trap of thinking there are few options open to us.

This happens a lot with jobs. If someone is frustrated, they think the only option is to quit.

Instead, if they were able to have a principled negotiation, it might be possible to find other approaches that might work better.

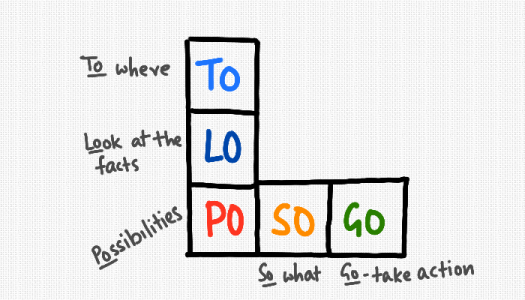

Generating options is about being creative – coming up with a range of ideas and working through them, perhaps using a framework such as TOLOPOSOGO.

This is where the idea of win-win comes into it. Alternatives that maximise each parties interests are more likely to go ahead than win-lose.

4. Insist that agreement be based on objective criteria

When we just can’t agree because our positions are directly opposed, then we need to find a form of objective criteria that we can both share and use to resolve differences.

The classic example here is when you share a cake between to children and they both want to cut and choose first.

Resolving this often means agreeing that one child cuts it and the other gets to choose first.

It might be possible to adapt a decision table to make this clear to both parties.

BATNA – the Best Alternative To a Negotiated Position

Sometimes we can’t agree, perhaps because the other side refuses to engage in the open way needed for principled negotiation or thinks that they can get their way through manipulation and dirty tricks – such as deception, trying to create artifical stress (banging the table, eating before a meeting and leaving you hungry) or leaking to the media.

In this situation, we need to call them out.

For example, if someone makes a take-it-or-leave-it type offer, then we need to treat that as a proposal and not simply accept the feeling of finality imposed by one side.

It’s also important not to have a bottom line, especially when there are imbalances in perceived power.

The only reason to negotiate is to get a better deal than one we can get if we didn’t negotiate.

That is our BATNA, the best alternative. Knowing our BATNA helps us make the most of what we have.

The power in negotiations comes from the ability we have, in the end, to walk away.