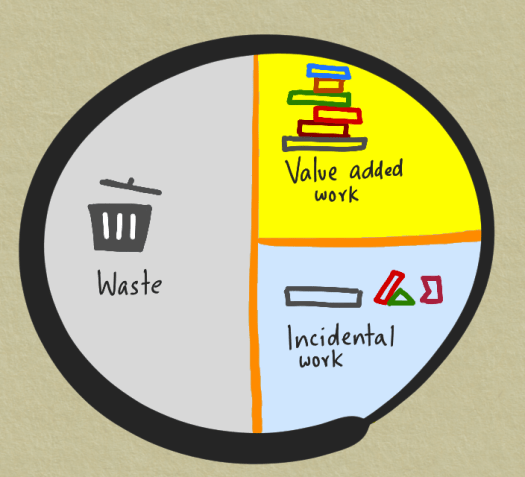

Taiichi Ohno, the man behind the Toyota Production System, believed that only a quarter of the work done adds value for the customer.

There are two linked words there – value and customer.

Some things that add value are seen by the customer – better service, making it cheaper and more simple.

Other things are not – improved safety, better screws, brighter tail lights.

What takes the other three-quarters of time?

Another quarter is incidental work, stuff loosely associated with the main value adding activities.

The rest is waste.

With physical systems – like making cars – we can focus on waste because it’s visible.

If there is excess stuff, it piles up. At home, if we’re buying the kids too many toys that’s clearly visible.

So we can focus on removing and eliminating waste wherever we can see it.

That’s easier said than done, especially when we need to get rid of stuff we already have.

But we can try and create rules and habits that mean less new waste is created.

In knowledge work, that waste comes in the form of emails and meetings and requests for long reports.

In this paper by Matthew May, he argues that because we can’t easily see waste piling up in knowledge work we need to focus instead on what work adds value.

That means working on our own lists of jobs before looking at our emails and responding to other people’s priorities.

It means avoiding all meetings.

It also means picking up the phone sometimes instead of sending out emails.

But that doesn’t really get to the point of it all.

The point is that there is a ratio between doing things that add value and everything else.

We’re trying to maximise that value to waste ratio – cut down the waste and increase the value.

At the same time, the size of the whole work package also needs to shrink.

It doesn’t make sense to do more. A lot of the time it actually makes a lot of sense to do less, to have less, to need less.

An attitude of removing, however, focuses our attention on the rubbish around us.

Which means we might miss the good stuff.

We should instead develop the ability to work on things that add value – and incidentally get rid of everything else.