Industry is rapidly adopting and adapting digital technology in modern manufacturing, in a trend sometimes called Industry 4.0 or the fourth industrial revolution.

This marks a change from “strong” machines to “smart” machines, as a network of connected devices with increasingly sophisticated technology add value and remove waste from manufacturing processes, supported by more monitoring and analysis capability for operators.

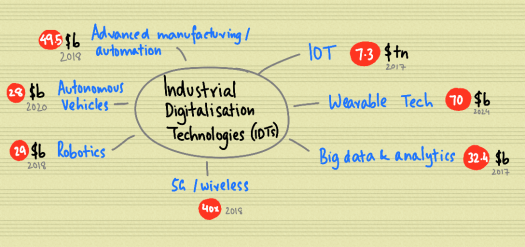

The Made Smarter Review looks at how UK manufacturing can benefit from using Industrial Digitalisation Technologies (IDTs) to boost manufacturing, growth and jobs.

The review argues that the prize is large. The global market for IDTs is already significant, in the region of trillons of dollars for Internet of Things (IOT) devices.

We are already seeing the increasingly widespread application of big data and analytics. A robust communications infrastructure, underpinned by 5G and wireless will make it easier for devices to talk to each other.

Advances in robotics, autonomous vehicles and advanced manufacturing are already being implemented and wearable technology is being seen as a huge growth area.

We will need more people with the skills and capabilities to implement IDTs.

In addition, the challenge with collecting increasing amounts of data is that you can end up with the same problem we have now with emails – humans have limited processing power and there is more coming at us than we can deal with.

There is little point in capturing lots of information if someone then has to look at it and intepret it before taking action. That simply creates a new bottleneck as human capability fails to keep up with the power of industrial systems.

The opportunities in these technologies will be unlocked when machines can work out when to take action based on the data they collect – from the “voice of the process”.

For example, a wearable tech heart monitor package may continuously monitor your heart and alert both you and your hospital if your readings go out of tolerance, and perhaps even check your diary and book an appointment for you.

A machine learning algorithm may be able to figure out a shift pattern at your facility based on your electricity or gas usage and calculate when to buy from the wholesale market in order to minimise total cost.

Digital competence is quickly becoming a “threshold” competence.

It’s something you have to have in order to compete and profit as the next industrial revolution gathers pace.

This review is a useful and comprehensive overview of what needs to happen in the UK to increase productivity, create new businesses, better jobs and make it more competitive globally.