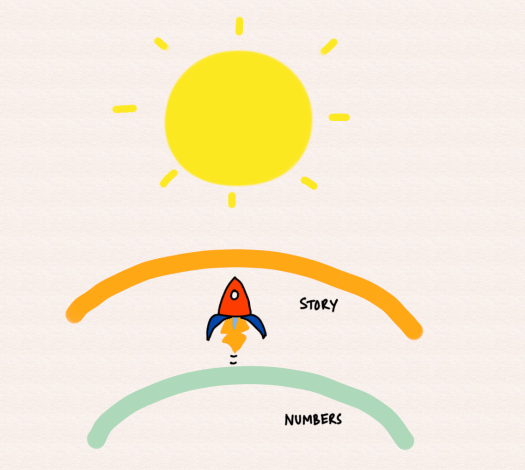

What value do consultants add to your organisation?

It depends on the kind of work you do and the resources you have in house.

The rule when adding someone external is that if you need something doing but don’t want to put your best people on it.

In that case, work with someone that’s willing to put their best people to work on that problem.

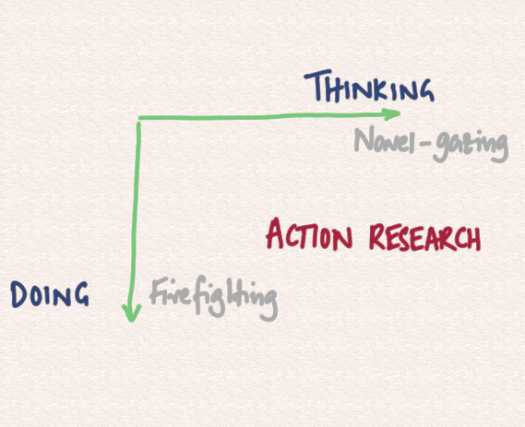

Which then brings us to the types of problems we face.

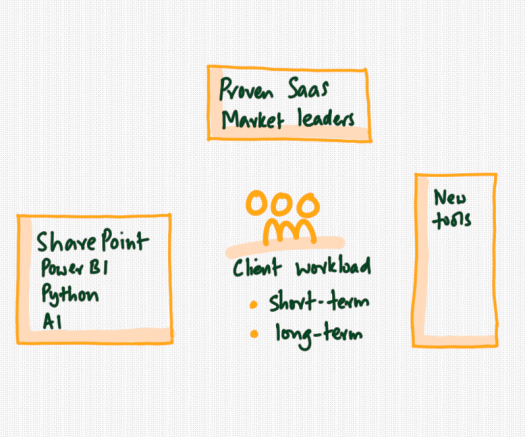

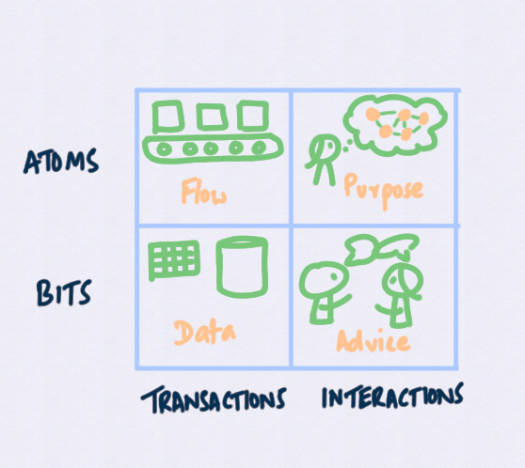

Some problems have to do with bits and transactions. Information and its use. So you bring in data services consultants.

It gets more difficult when you introduce interactions. It’s about information but also about how people make choices and operate in networks.

That’s where lobbyists, industry experts, networking groups live.

On the top left you have work that deals with atoms – problems of inventory, factory operations and energy usage.

Consulting work there is all about flow, about getting things moving more effectively and efficiently. Reducing costs. Moving product.

And at the top right you’ve got a mix of all these problems, bits, atoms, transaction and interactions.

That’s where it’s about having clarity of purpose – what you do and more importantly, what you don’t do.

Strategic consultants, the ones who’ve been there and done that and have the experience to help you avoid pitfalls operate in that segment.

Now it’s not really a simple 2×2 matrix. it’s more about how the four components: bits; atoms; transactions; and interactions, come together in a business.

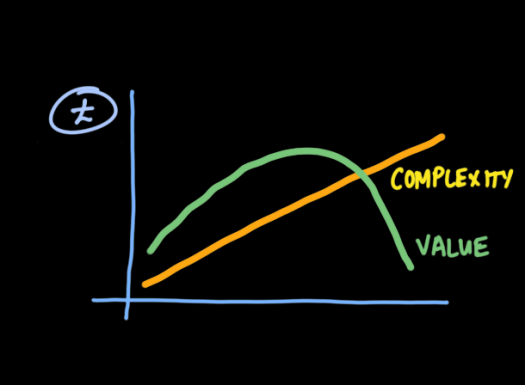

Consultancy, at its core, is a helping profession.

The idea is to help clients get things done that they need doing but shouldn’t be doing themselves.

We don’t need to make it any more complicated than that.