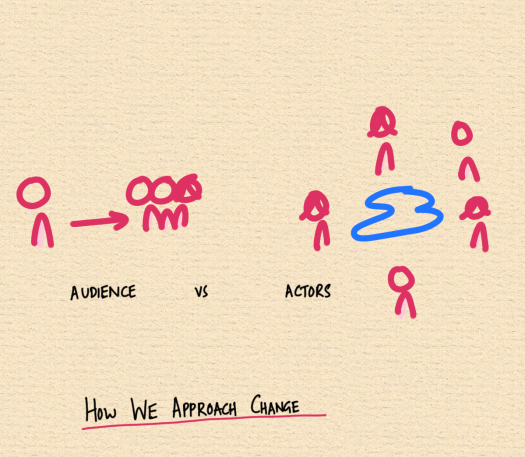

I come across two kinds of leaders tasked with driving change.

The first sees change as imposed. It’s a top-down, command-and-control process.

People are audiences – they are given a message and expected to act.

The second sees change as participatory and negotiated.

Stakeholders are actors with purpose and agency, and the ability to cooperate or resist change.

What matters here is building consensus and dealing with the messy reality everyone faces.

Which approach is better?

There is no right answer – it depends on the situation.

I love this quote by Poul Anderson – “I have yet to see any problem, however complicated, which, when you looked at it in the right way, did not become still more complicated”.

Change is not easy.

But it is a process.

Success or failure depends on how you design and run that process.