Success depends less on the structure you create than the story you tell.

When you’re working in a company does it often feel like the structure is working against you rather than for you?

I’ve been reading Jackson and Carter’s “Rethinking organisational behaviour: A poststructuralist framework” and think it has useful insights to sustainability managers – well, all managers in general.

It starts by getting clear on what we mean by structure.

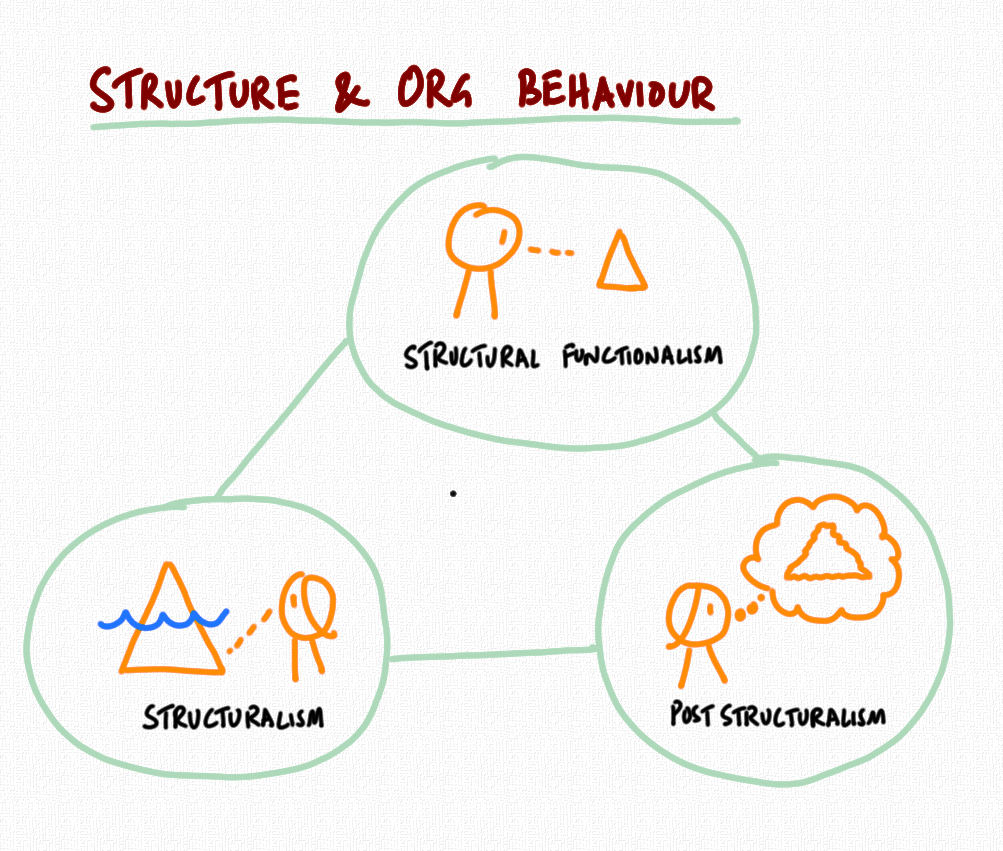

There are three versions of structure.

First, there is structral functionalism.

This view is that structure is visible, most clearly in the org chart.

You change things by getting the right structure. If things aren’t working, then restructure.

This is a dominant view – many people think it’s the “natural” way to think about organisations.

But – does it work? If you look at your organisation do you see visible structure getting results?

If not, we turn to structuralism for an explanation.

Structuralism says that it’s the stuff under the surface that drives behaviour – that which you don’t see but exists.

This is the underlying logic – the relationships and dynamics between leaders and teams that result in one thing or the other.

What makes a difference is the less visible stuff – power relations, inequalities, differing levels of freedom to act.

And then we have the third view – poststructuralism.

The first two approaches suggest that structure is a real thing and exists – either above the surface or below – but it’s there.

Poststructuralism says that structure is constructed – from the way we explain things.

Explanation is the key – it helps us make sense of what is going on.

That explanation is the structure, not real and objective but a product of the human mind.

If you’ve read this far and are wondering why this matters, this is why I think it’s important.

If the poststructralism view is right, then success depends not on the structure you create but the story you tell.

I’m sure you’ve heard of the famous Amazon process where people are asked to write a plan rather than use PowerPoint.

This could be seen as an implementation of poststructuralism – tell me a story – get your thinking down on paper and explain what you want to do and why it’s going to help.

Help me make sense of what is going on, so I can decide what to do next.