I’ve been making a conscious decision to put the phone away and read more – and I’ve just finished James Shapiro’s 1599 – A year in the life of Shakespeare.

This was an incredibly productive period for Shakespeare. He wrote Henry the Fifth, Julius Caeser, As You Like It, and drafted Hamlet.

The backdrop to his writing is equally interesting. An ageing tyrant was in power, the first Queen Elizabeth. The country was under threat of an armada from Spain and faltering under an Irish Rebellion – and the Queen was relying on a brash young noble, the Earl of Essex, to go in and sort it all out.

I wondered aloud to a friend if the world of today had parallels to the world of 426 years ago.

My friend, a history teacher, reminded me that such backdrops have existed for most of history – power and politics change little because people change little.

Shakespeare had to tread a fine line between saying things that had to be said – that were important to hear – and getting in trouble.

It was a world of censorship, one where books and plays were seized and destroyed if they were considered dangerous.

We know very little about how Shakepeare navigated the politics of the day or his personal views on anything – the richness of his surviving work is only equalled by the lack of information on him as a person.

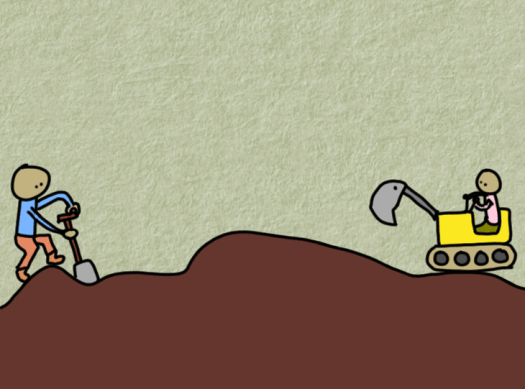

He must have been good at what he did, however, because he did the work – he wrote his plays, he acted in them, he ran a business – and what he created still helps us make sense of the world.

If you have things to do, for example as Hamlet did, you’ll succeed if and because you have cause and will and strength and means.