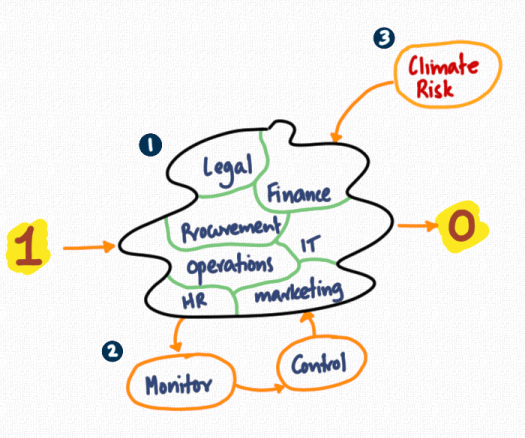

The model for decarbonising business is arguably quite simple.

Take a company with emissions of 1 or more, and make that number 0.

The devil is, as always, is in the detail.

How can we stand back and look at the situation facing organisations today?

The first thing is to recognise that making an organisation more sustainable is not a departmental activity – it requires coordination with all the main functions.

The sustainability team has to work with legal, finance, procurement, IT, operations, HR, marketing and others and get them aligned on the way forward.

But the first question anyone asks is “where are we right now, what does the data say?”.

So the starting point is often the second step – we need to monitor the organisational system – and that starts with collecting data and creating a robust and reliable data set.

Ten years ago, this was an annual exercise that no one worried about too much. You had different reasons for collecting this information, depending on the market and schemes you were part of, but it was really an end-of-year exercise.

If you want to make decisions on the data, however, if you want to use it to take control action on the organisational system, then you need it more frequently – so that’s a harder thing to put in place.

But we have the systems and technology to do that now.

Some people worry that we’ve gotten stuck at this step – collecting and reporting, but taking no action.

But taking action is a non-trivial problem and goes back to step 1 – we have to get the key decision makers, the people with power, aligned first.

And there are other factors that influence their decision making – what customers think, what the regulations say, what employees want, what’s the best use of money right now?

It takes a lot of talking, lots of engagement, to get some clarity on this.

In the meantime, the climate keeps changing.

There is a definite shift in the mood music – from an attitude of we can solve this to what do we do if things start going bad?

There is more talk about the third element in this picture – the exposure to climate risk.

Depending on who you are and what you do the impact from climate change could be nothing, or pose an existential threat to business.

A major emerging risk to solar panels, for example, is extreme weather, with hail and wind risk factored into insurance premiums for developments.

The stuff we’re focus on right now – the carbon accounting – is just the basics. It’s what we have to do to be able to have a proper conversation based on data and evidence.

Those conversations, the engagement with leaders in organisations on which decisions need to be made – that’s where the real work is.