Thursday, 9.12pm

Sheffield, U.K.

Every company has two organizational structures: The formal one is written on the charts; the other is the everyday relationship of the men and women in the organization. – Harold S. Geneen

I write a lot in this blog about soft systems methodology (SSM).

But what is that, exactly?

To find out, you might want to read Peter Checkland and John Poulter’s “A short definitive account of soft systems methodology and its use for practitioners, teachers and students”, published in 2006.

It’s the definitive account, the final say, so perhaps that’s a good place to start.

A few of Checkland’s papers complain that people don’t understand SSM and they miss the point of it in how they use it – or claim to use it.

It’s easy to get lost in the academic discussion – but I am going to make things worse by attempting my own interpretation of what’s going on with SSM.

Here’s my version of the brief version.

Let’s start with life itself – the everyday. Today, tomorrow, yesterday. All the days that we live through.

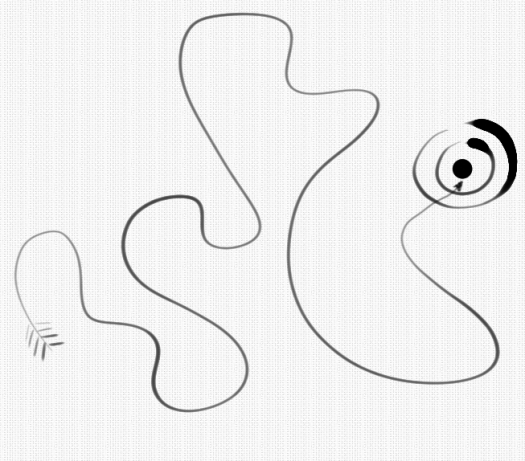

We live in a flux of interwoven events and ideas. Ideas lead to events, events spark ideas and life goes on.

Everyday life produces situations.

These situations have people in them. It’s the presence of people that make it possible for situations to exist – because they come into existence in the minds of people. A problem only bursts into existence when someone believes it does.

Let’s not worry about this too much, but the key point is that you need people to make a situation – and what those people think about the situation is what we’re focused on.

Sometimes, they think a situation is problematical. That something is wrong. That things could be better.

Why do they do that? Why look for problems, or think at all?

It’s because we can’t help but be purposeful – we act with purpose. Human beings have a brain that allows them to act intentionally – rather than randomly.

But, we usually only see situations from our point of view. We may exist in a complex, multifaceted reality that some people insist is very simple because they see it one way, and others disagree because they see it another way.

It’s the same thing – we just have different perceptions of the thing we’re in.

Wars have been fought over these different perceptions of the same thing.

But, we’re learning over time – and the thing that could help is to learn more about the situation.

We go out and intentionally learn more about the situation as perceived by the people affected by it and affecting it.

We talk to them, we ask questions, we listen to them, we build a rich picture of what’s going on.

All this learning helps us build models of purposeful activity.

This is a new bit – it’s not something most people do.

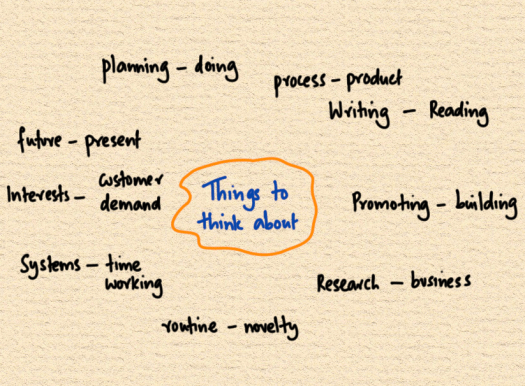

A model helps us capture that learning and put it into a form that we can look at and understand – it’s like a theory, an operating manual – something we can use.

And we use it to help us as questions about the situation, to take this model or models with multiple viewpoints and have a structured debate – a good conversation about what’s going on and what we could possibly do.

This kind of discussion helps us to decide what action to take – and to take that action.

The action, we hope, is going to improve the situation.

It’s going to affect it in some way, anyway.

And now the situation has changed – hopefully for the better, sometimes for the worse, and we now have a new situation.

If all is good, great.

If it’s still problematic, then we continue our cycle of learning, modelling, questioning, and taking action.

All this may seem simple. Perhaps even obvious. But it’s the result of decades of thinking and action research.

In my next post I think I need to go back to where it all started to show the gap between where things were and where things are, and then build a bridge between the two.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh