Saturday, 2.15pm

Sheffield, U.K.

Statistics are used much like a drunk uses a lamppost: for support, not illumination. – Vin Scully

It’s normal, I suppose, to come to the end of a year and look back to see what has happened and what has changed.

I’ve written more this year, around 60,000 words. Far short of the 280,000 I clocked in 2020, but a better showing than the last couple of years.

I also have this sense of being buried under material. Notebooks full of stuff, notes from everywhere, from stuff I’ve done, stuff I’ve read, journals that chronicle the mundane everydays.

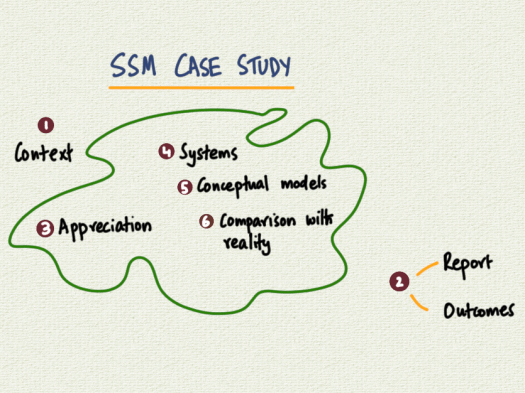

How do writers make sense of all their material? How do they work through these ideas and get them into a form that says something useful?

My favourite author, Robert Pirsig, gives us a sense of this in a rare talk, as he describes writing his book Zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance. How the book was something he had to write. How he wrote a draft. Hated it. Put it away for a couple of years. Then wrote it again – and how this time, it came out exactly right.

The sequence that one goes through, the germ of an idea, the flailing around in the darkness, the collecting of ideas and thoughts, trying to piece them together, failing, waiting, then starting again and making sense – that’s something that we go through as humans.

Will these new tools we have – the AI assistants – help us do this better or will they make us less capable of putting in the time and work needed to go through this process?

After all, if I can jot down some notes, or copy what others have written into a file, and get the AI to group and summarise what’s going on, isn’t that the same thing that I’ve spent all this time doing?

Probably.

I think that we’ll increasingly hand over stuff that isn’t worth doing to these tools.

Reading and summarising a whole canon of ideas – maybe that’s something we leave to the AI.

Although, we don’t really need it – that’s what encyclopedias have always done. Or the introduction and literature review of a decent paper. That’s going to have the same kind of material.

The work we’ve got to do is the stuff that hasn’t already been done, or that can’t be done because there isn’t enough data to build a statistical model that can fit the existing data and predict what comes next.

If what you do can be reduced to statistics then the machines will do those faster and better over time.

Maybe that’s helpful.

What they won’t do is the stuff that can’t be statistically modelled.

I learned a decade ago that sustainable competitive advantage comes from rare, valuable, inimitable capabilities that you have the organisational structure to deliver.

I think we might need to add unpredictable to this list.

VRIOU.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh